Introduction to architectural sculpture

The decoration of public buildings with sculpture was not uncommon in the ancient world, but in Greece, where it is almost confined to sacred and few other public buildings, it has a special significance, not least for its subject matter. Its placing is determined by the main orders of architecture.

- Pediment of the Megarian treasury at Olympia c. 510-500 BC

- Drawing of Doric order

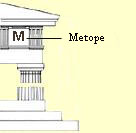

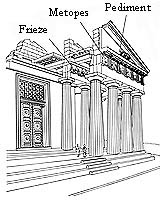

Thus, in the Doric order, there may be groups in the pediments at each end of a temple, panel reliefs in the metopes around the upperworks of the outside of the temple, and free-standing statues at the apex and corners of each pediment (akroteria).

- Drawing of Ionic order

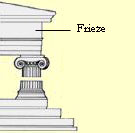

In the Ionic order pedimental sculpture is rare but there may be a continuous frieze around the upperworks of the outside of the temple.

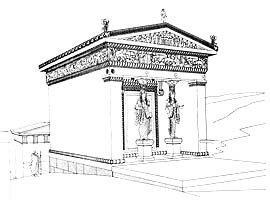

On smaller buildings, such as the Archaic Treasuries at Olympia and Delphi, the sculpture can be quite lavish but still determined by the architectural orders. From the 4th century on the larger altars and individual votive monuments may be decorated with appropriate friezes.

- Cutaway diagram of east side of the Parthenon

Generally all such decoration is high on the building, and with time what seems peculiar to one order - such as the Ionic frieze - may also be incorporated in a Doric building (as in the Parthenon above). Occasionally the oriental practice of using a human figure as a column appears ('Caryatids').

- Reconstruction of the Siphnian Treasury

- Caryatid from the south porch of the Erechtheion

Where the subject matter is narrative it is generally chosen to demonstrate the god of the temple, possibly in action or simply epiphany, or there is a myth scene which is related to the cult or city. Sometimes the relevance is very hard for us to determine.

The following account, roughly chronological, draws attention to the principal complexes and their subject matter. The style of the sculptures corresponds with that of free-standing works but is often the best evidence we have for any period, and avoids the problems of 'original' and 'copy' as well as being more easily datable.

Archaic

Some 7th-century Cretan buildings are decorated with friezes in an oriental manner. Many 6th-century buildings fill their pediments with figures of fighting animals, and there is often a Gorgon at the centre. These are primeval statements of power but may be accompanied, in a subsidiary position, by small narrative groups. Such were the pediments on the Artemis temple at Corfu and on the buildings of Athens Acropolis, culminating in one with marble pediments, showing both the animal fights and the fight of Gods and Giants, which had been given an Athenian message.

- West pediment of the temple of Artemis at Corfu. c. 600-575 BC

At Assos, near Troy, the Doric temple has much in common with mainland rather than east Greek work, yet has friezes with myth subjects.

Of the later Archaic temples, that of Apollo at Eretria has subjects that seem to relate more to Athens (politically and geographically close) with Amazon fights and Theseus.

At Aigina the assimilation of the goddess Aphaia to Athena allows Trojan scenes where Athena dominates but some heroes have Aiginetan associations.

- Model of west pediment of the temple of Aphaia on Aigina c. 490 BC

The Treasuries at Delphi, one Doric for Sikyon, one Ionic for Siphnos, have a rich variety of myth scenes of which only the unusual pediment for the Siphnian has a clear Delphic association (the rape of Apollo's tripod). The Siphnian has statues of women (Caryatids) for its front columns - see previous page.

- Cast slab of east pediment of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi. c. 525 BC.

Cast No. A012

- Metopes from temple C at Selinus. c. 550 BC

The Greek colonies in the west have Doric buildings with rich mythical subjects in metope series, as that from Selinus in Sicily and the sanctuaries at the mouth of the River Sele near Paestum.

Classical

- West pediment of the temple of Zeus at Olympia c. 470-457 BC

The early Classical temple of Zeus at Olympia has pedimental subjects which relate to Zeus, as guardian of oaths, and Apollo, as upholder of law (at the battle with the centaurs, above).

- Cast of Olympia metope No. 10.

Herakles supports the heavens as Atlas brings the apples of the Hesperides.

Cast No. A069

Herakles, associated with the foundation of the sanctuary, is represented by his Labours set in metopes placed unusually over the porch doors and not over the outer columns of the temple.

The mainly Doric buildings of Athens' building programme from the mid-5th century to its end carry scenes more related to Athens' history, through myth, than to cult. The Hephaisteion metopes share the honours between Theseus and Herakles, at one end of the temple only; it also introduces friezes over the inner porch walls, with what seems to be an Athenian mythical encounter, and a centauromachy (below). This placing of friezes in the porch appears also in a new temple at Sunium.

- West frieze of the temple of Hephaestus in Athens. c. 430 BC

The Parthenon carries this use of friezes further by placing a continuous frieze round the whole central block of the building. The sculpture subjects seem to relate closely to the building's subsidiary role as celebration of Athens' success against the Persians: the birth of Athena and her winning the land of Attica in the pediments; metopes with Amazon fights, the sack of Troy, centauromachy, and the Gods fighting Giants -

- East pediment of the Parthenon. The Basel reconstruction (by Berger)

- Casts lab of the west frieze of the Parthenon

- and the frieze with a heroic procession of cavalier citizens led to the presence of the Twelve Gods.

- Caryatids in the south porch of the Erechtheion

There were also new Ionic buildings on the Acropolis at Athens: the Erechtheion has a mysterious frieze which perhaps showed early heroes of Athens and their cult. Its south porch has figures of women (Caryatids) instead of columns.

- Cast slab of west frieze of the temple of Athena Nike at Athens

Cast No.A101a

The other Acropolis Ionic temple was for Athena Nike (Victory), with friezes of the Twelve Gods, and three of fights, including one with Persians.

- Cast slab of the frieze of the temple of Apollo at Bassai.

Cast No. A107

At the end of the 5th century the Doric temple of Apollo at Bassai has characteristic canonical metopes outside but places a frieze around the inner walls of the interior room - fights with Amazons and centaurs, attended by Apollo and Artemis.

- Cast of woman on horseback - acroterion of the temple of Asklepios at Epidauros.

Cast No. A127

In the 4th century the schemes are similar. The most notable are fragments of pediment at Tegea and acroteria of riders at Epidauros.

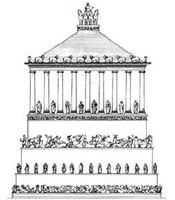

- Reconstruction of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus by G.Waywell/S.Bird.

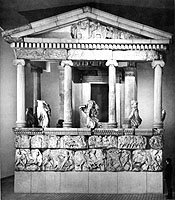

A strongly hellenized style develops in nearby Lycia, again for tomb monuments. The Nereid monument is Ionic but has a full array of pedimental sculpture and of friezes both on the building and on its base.

- Reconstruction of the Nereid monument in the British Museum

Elsewhere in Lycia a tomb enclosure at Trysa is decorated with friezes showing a wide variety of Greek myth. It is characteristic of Lycian architectural sculpture that, beside the myth, there are scenes of near-contemporary military action (city-sieges) and of the monarch in his court, the type of subject not seen in Greece proper.

- Cast slab of tomb enclosure at Trysa showing detail of siege.

Cast No. A120d