Introduction to grave monuments

The relief gravestones of the Greek world created a mode for commemoration of the dead which has influenced funerary art in the west to the present day. It started, however, in a manner easily paralleled in other cultures, where the desirability of marking a grave was recognised, if for no other reason than to ensure it was not disturbed. This marker, which in 8th-century Greece and thereafter need be no more than a large vase, was more commonly a stone slab. The addition to the slab of the name of the dead and shaping of the stone into human form can be documented in 7th-century Greece though it was not widespread.

- 7th c. gravestone from Thera, with the name of the dead

- 7th c. gravestone from Kimolos, roughly shaped in human form

- 7th c. roughly shaped limestone from a cenotaph on Thera.

In the continuing history of gravestones two basic types emerge - figures in the round, notably the archaic kouroi and korai, and relief gravestones (stelai) with one or more figures. These at first represent the dead generically, the identity being given by inscription. Athens and Attica dominate the story but there are important local variations and inventions.

Archaic grave markers

Figures in the round

Small.jpg)

- Kouros from a cemetery in Attica. Early 6th c. BC.

The male kouros type and the female kore, which are archetypal archaic figures, served both as grave-markers and dedications in sanctuaries. In Attica the series starts about the beginning of the 6th century BC and continues into the early 5th century but is rare thereafter.

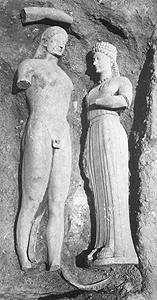

- Kouros and kore from Attica (Myrrhinous).

The two statues (left) had been damaged and buried together in antiquity. The kore's base is preserved: she is Phrasikleia who will 'ever be called maiden, the gods allotting her this title instead of marriage'. About 550 BC.

Attic relief gravestones (stelai)

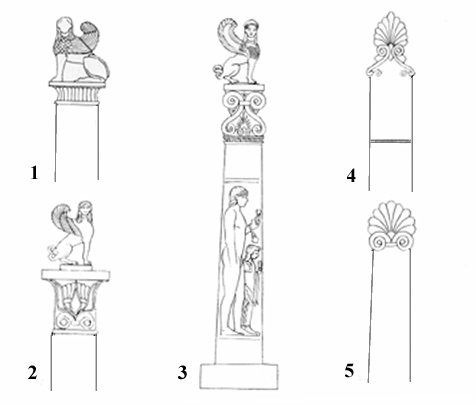

In Attica, around 580 BC, a series of tall gravestones begins, topped by the figure of a sphinx, on a simply decorated capital. After the mid-century the capital is elaborated as palmettes with spirals, but soon thereafter the stele type is simplified, with a palmette only. The type disppears in the early 5th cent. BC. Most figures are male and there is rough age differentiation by type: young as athlete, mature as warrior, old as man with dog. In the last phase the rectangular bases for the stelai may be decorated in relief on three sides.

Attic gravestone types

- The sequence of Attic stelai (after Richter): 1 - New York; 2 - sphinx in Athens and capital in New York combined; 3 - New York; 4,5 - painted examples, Athens and New York

- Sphinx and capital, from Attica. About 540-530 BC.

- Cast of kouros base with relief scene, from Athens. Side A - a ball game. About 510 BC.

Cast No. D 007a

-

Cast of stele of Aristion from Velanideza (Attica). About 510 BC.

Cast No. D004

Non-Attic relief gravestones

Most follow the Athenian pattern, but double sided reliefs are found in north Greece and the general Attic type continued through the Early Classical period, beyond the middle of the 5th century, when Attica is no longer making relief stelai for graves. There is more variety of figures - more women and children.

- A two-sided gravestone figuring Artemis, from Dorylaion (north west Anatolia). About 525 BC.

- Gravestone for the brothers Dermys and Kittylos, from Tanagra (Boeotia). About 580 BC.

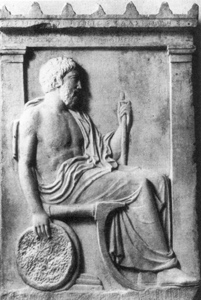

- Cast of gravestone for an old man, from Boeotia, made by Alxenor of Naxos.

About 490 BC.

Cast No. D017

- Gravestone for a woman, from Crete. About 490 BC.

- Cast of a gravestone for a woman, shown with a companion or attendant. About 460 BC.

Cast No. D 027

Classical grave markers

Attic gravestones

The series recommences in about 430 BC, possibly stimulated by the presence in Athens of many masons who had been employed on the new public buildings such as the Parthenon, but also answering a new need for personal memorials. The grave reliefs are more often rectangular now, with a pedimental top, and in the 4th century the figures are carved often in very high relief, almost in the round, and the monument may be built with projecting wings which may themselves carry reliefs. In the later 4th century a decree by the governor of Athens, Demetrios of Phaleron, brought an end to the series of decorated reliefs.

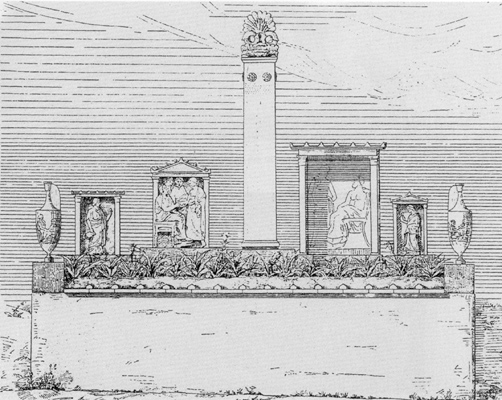

Women dominate the scenes, in quiet domestic situations or bidding farewell, sometimes to a warrior husband. Often there is simply a scene of quiet contemplation, seldom of active mourning. A few commemorate death in battle, but Athens' war dead were buried separately with stelai which listed their names and had small reliefs of fighting on them. Family graves were marked out in the main Athens cemetery and may be embellished by other sculpture in the round, animals or mourners. The mourning siren begins to appear as a motif for funeral art.

- Reconstruction of a group of graves in the Athens cemetery, for a family of wealthy immigrants from the Black Sea

- Gravestone of Ampharete in the Athens cemetery. About 410 BC.

- Gravestone of Eupheros in the Athens cemetery. About 430 BC.

- From Athens a gravestone of Sosinos, a copper smelter, with an ingot. About 400 BC.

- Cast of gravestone of Dexileos, who was killed at Corinth in 394/3 BC.

Cast No.D 067

-

Cast of gravestone of Demetria and Pamphile. About 320 BC.

Cast No. D077

- Cast of gravestone from near the Ilissos, Athens. About 330 BC.

Cast No. D076

- Figure of mourning slave from a grave monument near Athens (Menidi).

4th century BC.

Non-attic gravestones

The non-Attic gravestones follow the tradition started in the archaic period without much further reference to Attic styles.

- Gravestone for a woman (Apollonie) shown with her family. From Ikaria (east Aegean island). About 460 BC.

- Cast of gravestone

of a girl, from Paros.

About 450 BC.

Cast No. D031

- Cast of stele, showing a horseman, from Thespiae (Boeotia). About 440 BC.

Cast No. D034

- Gravestone of Krito and Timarista, from Rhodes. About 400 BC

Sarcophagi

Painted clay sarcophagi and simply decorated stone sarcophagi are known from the Archaic period, from East Greece, and this is the area also where stone relief sarcophagi also appear, although rarely. An important series executed by Greek sculptors was made for the graves of Phoenician kings at Sidon in the 5th and 4th centuries, during Persian rule there.

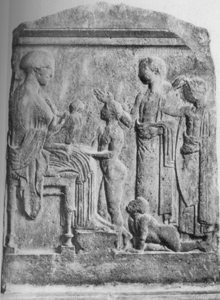

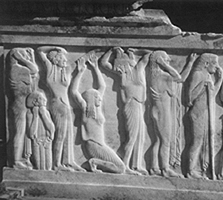

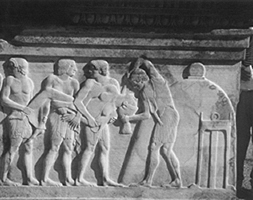

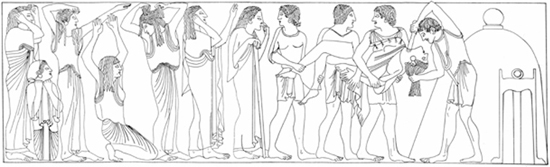

Sarcophagus from Canakkale, near Troy.

Decorated with mourning scenes and the myth of the sacrifice of Polyxena at the tomb

of Achilles. About 500 BC.

- Drawing of the above scene

- Sarcophagus, probably from Cyprus. Decorated with scenes of Greeks fighting Amazons on all sides. About 360 BC.

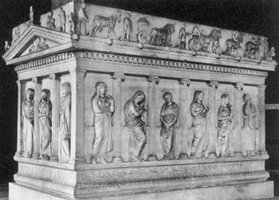

- The 'Mourners Sarcophagus' from Sidon. About 360 BC.

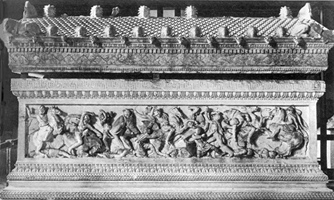

- The 'Alexander Sarcophagus' from Sidon. About 315 BC.

Anatolian monuments

The native states of Anatolia, in Caria and Lycia, under Persian control in the 5th/4th centuries BC, were strongly influenced by Greek style in the decoration of their grave monuments, which are unlike the Greek in being mainly above-ground and often architecturally elaborate. Early examples and the Mausoleum were carved by Greek artists, but many in Lycia have a distinctive graecizing style developed locally.

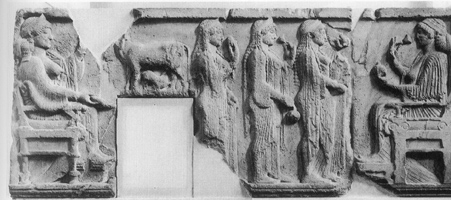

- The 'Harpy Tomb', from Xanthos. About 470 BC. The reliefs were set at the top of a high pillar.

- Cast of woman running, nymph or Nereid.

Cast No. A116

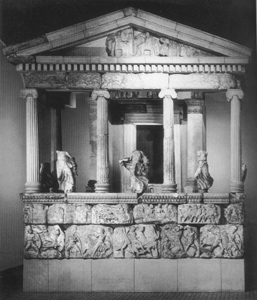

- The 'Nereid Monument', from Xanthos, Lycia. Early 4th century BC. A tomb in the form of a temple on a raised base.

- Cast of woman running, nymph or Nereid.

Cast No. A117

- The 'Nereid Monument' reliefs show court scenes, hunting and fighting.

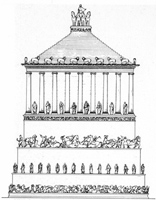

The Mausoleum at Halikarnassos. Mausolus was a Carian king. The tomb, which gives its name to all 'mausolea' is four-square on a raised base, with relief and in-the-round sculpture executed by invited Greek sculptors rather than local Ionian ones. Mid-4th century BC. The sculptures are in London.

- Reconstruction of the Mausoleum at Halikarnassos. About 300-350 BC. G. Waywell/S.Bird

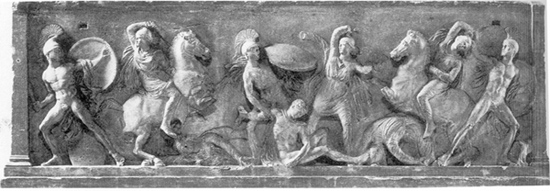

- One relief panel from the Amazonomachy frieze of the Mausoleum

- Cast of one relief panel of Amazonomachy frieze.

Cast No. A138

- Cast of statue of 'Mausolus', a Carian prince.

Cast No. B097c

Casts of an Amazon and a charioteer from the Amazonomachy and Chariot friezes.

Cast Nos. A139 and

A140

Lycian tomb of Payava

This is the commonest Lycian type of the 4th/3rd century BC.

Lycian tomb and Sarcophagus. About 380 BC.

- Sarcophagus

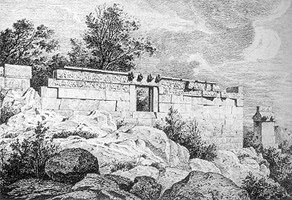

The tomb enclosure at Trysa, Lycia

The enclosure is decorated with a double frieze, in and out, mainly of Greek mythological scenes. The sculptures are in Vienna.

Trysa. The heroon. About 390-380 BC.

- Cast of a slab from the west frieze showing a city under siege. Defenders on top of the walls.

Cast A120d

Hellenistic gravestones

Relief gravestones of the 3rd-1st cent. BC are almost wholly confined to the East Greek world. The commonest type is tall, with a fine architectural setting, and a big figure of the dead with small attendants. Another type, a broad rectangle, presents the dead as a hero, usually at a feast - the 'Death Feast' or 'Totenmahl' reliefs.

- Gravestone of an athlete, leaning on a herm and with an attendant. From Rhodes. 3rd century BC.

- Gravestone of a princess with attendants, a tall torch and a cornucopia on a pillar. 2nd century BC.

- Gravestone of a youth shown as a hero at hunt, with his horse, dog and attendants. From Smyrna. 3rd/2nd c. BC.

- Gravestone of a man, shown at feast with his wife and children. From Byzantium. 2nd/1st c. BC.