The Classical period (5th - 4th century BC)

- Youth (the 'Kritian boy), from Athens Acropolis. About 480 BC

Cast No. B068a

In the early 5th century Greek artists began consciously to attempt to render human and animal forms realistically. This entailed careful observation of the model as well as understanding the mechanics of anatomy - how a body adjusts to a pose which is not stiffly frontal but with the weight shifted to one side of the body, and how a body behaves in violent motion. The successors to the archaic kouroi, mainly athlete figures, are thus regularly shown 'at ease', one leg relaxed, with a complementary shift in the shoulders, and the whole emphasized by contrasts of rigid and relaxed in limbs.

- Metope from the temple of Zeus, Olympia. Athena and Heracles recover the apples from Atlas. About 460 BC Cast No.A069

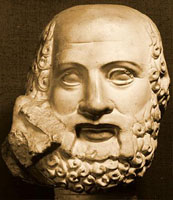

- Head of a seer from the east pediment of the temple of Zeus, Olympia.

About 460 BC

Cast No.A050

The new style is best expressed in the Parthenon marbles of about 450-435 BC but there was a preceding style of some importance - the Early Classical, sometimes called the Severe Style, which is exemplified in the sculptures for the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. Here the figures are mainly lifelike but drapery forms are plainer (a change from the archaic Ionian chiton to the more austere peplos for women), and there are deliberate attempts at depiction of emotion in faces and of different ages in rendering of bodies.

-

Reclining figure of Dionysos from the east pediment of the Parthenon. About 430 BC

Cast No. A091

- Reclining figures of Dione and Aphrodite from the

east pediment of the Parthenon. About 430 BC

Cast No. A094

- The 'Dresden Zeus'. Copy of a statue of about 440 BC

Cast No. C049

These innovations were foresworn by Pheidias, in his design for the Parthenon, and replaced by a more idealized realism in which body forms were often more regular than in life, and heads, except for monsters like centaurs, seem passionless, calm. Dress, after the austerity of the Early Classical becomes dramatically realistic. But the Parthenon is the fullest expression of what is sometimes called the High Classical. It is in this period and style too that, in the following hundred years, many of the basic types for the Greek gods were devised, and these remained influential throughout antiquity.

- Bronze Zeus from Cape Artemision.

About 460 BC

Cast No. B072a

The new realism could not be achieved by the old techniques of carving directly into a stone block, but had to be based on a modelling technique, building up the figures in clay on armatures, like a skeleton, and then copying into stone. The same technique was required for making bronze statues, which begin to be important, at life size, from the early 5th century, though few have survived.

- Copy of the Doryphoros of Polykleitos, about 440 BC

Cast No.C032

Athens was not the only source. Olympia in south Greece has been mentioned, and there were distinguished sculptors from elsewhere, such as Polyclitus, with their own variations on the idealized norm. The Persian invasion of Greece and sack of Athens (480/479 BC) discouraged much work in Athens for some 30 years, but the city was the leader of a League against the Persians and rapidly grew wealthy again. Although the Persian Wars were a watershed in Greek fortunes they probably had no effect on the arts, other than to help Greeks recognize the new 'classical' mode as more appropriate to themselves than to the 'barbarians' they had repulsed. But the Parthenon is in its way commemorative of success over the Persians and political choice begins to determine much public sculpture.

- Gravestone from Athens. Early 4th century BC

Cast No. D069

The tradition of the archaic grave reliefs is continued outside Athens, where the practice resumes, in the new style, only towards the end of the 5th century and through the 4th, until halted by a decree against luxury. The reliefs, in the new style, well exploit the calm realism of the figures which for the most part depict the dead as in life, in the calmer moments which may imply a farewell, and they include the best classical studies of women.

- Victory (Nike) by Paionios, at Olympia. Celebrating a victory over Spartans at Sphakteria in 424 BC.

Cast No. B086a

War also promoted grander monuments celebrating success, placed in the major Greek sanctuaries of Olympia and Delphi, where also there are the many athlete statues and groups for victors in the Games.

The end of the 5th century is marked by Athens' defeat at the hands of fellow Greeks, followed by the rise in importance of various Greek Leagues of states, and, in the north, the growing power of Macedonia. This meant the production of more civic monuments, and even, for the Macedonians, royal family groups.

- Portrait of Socrates.

Cast No. C145

4th-century styles develop from the 5th-century, still idealized realistic, but bolder in poses and beginning to create interactive groups which lent a further degree of depth to the rendering of subjects such as battles or hunts. Individual realism, rather than generalized, is picked up again after the experiments of Olympia. Real portraiture emerges, at first of the dead only, and interpreting character as much as physiognomy, but soon quite realistic. Emotion is more readily portrayed also, though it takes a long time for women's heads to be shown as more than conventional masks.

- Copy of the 'Tyrant Slayer'

Aristogeiton, about 475 BC

Cast No. C006a

As in the 5th century, much of the best work was done in bronze, but for the most part we have to judge style from surviving marbles (usually from architecture) or the many close copies made of earlier works for Roman patrons, which fill most museum galleries today and are well represented in Oxford.

- Copy of the Knidian Aphrodite

by Praxiteles. About 350 BC

Cast No. C172

One new use of marble was for the female nude, since, althoguh statues were still all painted, the flesh-like qualities of polished marble were appreciated, and we get the first sensual studies of the female body, a trend started by the sculptor Praxiteles and his famous Aphrodite - lost to us except in poor copies.

- A Lycian king. From the Mausoleum

at Halicarnassos. About 350 BC

Cast No. B097

In Anatolia, now dominated by Persia, Greek sculptors still worked for the hellenized princes, in homeland styles, as on the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, or encouraging local schools, as in Lycia. The Western Greeks are less active, though prosperous, and especially develop 'acrolithic' statues, heads and flesh parts in the scarce or imported marble, the rest in cheaper material, stone or wood.

-

Frieze from a grave precinct at Trysa (Lycia).

Early 4th century BC

Cast No. A120c

-

Head of goddess; S. Italy. About 470 BC

Cast No. B082

'The 4th century' is not a style as the Classical of the 5th century had been, and in some respects the sculpture seems to be marking time before dramatic development in the following period. Pure realism is in its way an end in itself and any development from it has to abandon some of its basic principles.