Portraits

The identification of statues with individuals did not involve actual portraiture, rather than generic types (old, young, warrior, etc.), until the advanced Classical period. Even in the 5th century BC this was the usual practice, with minimal acknowledgement of individual features, except for one or two Early Classical portraits, and some work in other media (gems) in the East Greek world, where types other than the idealised realistic were adopted. Examples are the Themistocles head, and gems by the Chian engraver Dexamenos; while the poet Anacreon, dedicated on the Athenian Acropolis, is simply characterised as a bon viveur. (Until the advanced Hellenistic period portraits are of full figures, not heads alone, and except for some Hellenistic, almost all are known only from copies of the Roman period, when they were made for intellectual clients.)

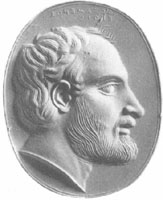

- Head of a man, on a jasper gem, made by Dexamenos of Chios. 450-425 BC

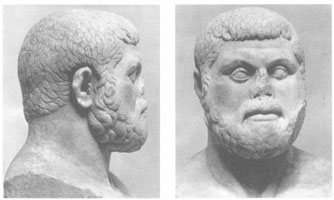

- Head of Themistocles; copy of an original of 475-450 BC

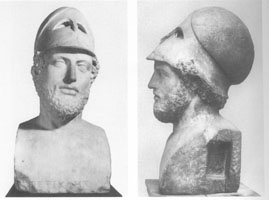

- Head of Pericles, by Cresilas. Copy of an original of about 425 BC

- Portrait of Anacreon; copy of an original of about 440 BC

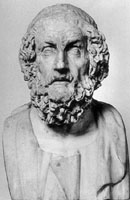

At the end of the 5th century BC there is some evidence, mainly from texts, for real portraiture, but down to the mid-4th century it tends to be of the long-dead (Homer and others) or of the recently dead, and often much depends on interpretation of the character of the dead (Homer, as blind and wise; Socrates looking like a satyr) rather than any real knowledge of the subject's features

- Portrait of Homer 4th century BC

- Portrait of Socrates. Late 4th century BC

- Portrait of the playwright Euripides, about 330 BC

- Portrait of the orator Demosthenes, by Polyeuktos, early 3rd century BC

The Hellenistic period sees a considerable interest in the production of portraits of past worthies, especially writers and philosophers, for many of whom stock body types are devised.

- Portrait of the poet Poseidippos, late 3rd century BC

- Portrait of the philosopher Chrysippos, late 3rd century BC

Accurate, though sometimes psychologically interpreted, portraiture of contemporaries, includes not only the Hellenistic Greek rulers, whose heads also appear on their coins which are often the only means of identity, but of private persons. Family likenesses are observed sometimes in the types for royalty, and Alexander's portrait in particular served as a model for folk with similar aspirations. Portraits remain relatively rare on tombstones.

- Portrait of King Philetairos of Pergamon, mid 3rd century BC

- Bronze portrait of Hellenistic ruler. 3rd/2nd century BC

- Portrait of Alexander the Great, made about 330 BC

- Portrait of King Antiochos III of Syria, mid 2nd century BC

- A Roman businnessman, from Delos. About 100 BC

- Portrait of a priest (?) from Athens. 1st century BC