Cameo Corner, the American Millionaire and the Marlborough Gems

Cameo Corner was the principal centre for the sale of jewellery in London for the first half of the twentieth century. It was located first at 1 New Oxford Street, and after the Second World War in Museum Street – always within easy reach of the British Museum. It had been founded by Mosheh Oved (alias Edward Good) who had emigrated from Poland as a watch-maker to seek his fortune in England. In this he was successful, becoming one of the busiest dealers in jewellery and attracting important and regular customers.

His was a colourful and imaginative character, strongly conscious of his Jewish ancestry, and himself a co-founder of the Jewish Museum in London (the Ben-Uri Museum). He wrote several books on aspects of his life and Jewry in Europe, and especially a series of memoirs, assembled in a single volume Visions and Jewels published first in Hebrew, then in an English translation (1952). It is not at all a systematic work and is full of anecdotes, not always connected with his trade. His vivid descriptions of his customers and their motives and behaviour lend it a special charm, but in common with many dealers he was at some pains to disguise their identities. In this he was successful naming among few others only Queen Mary, and even remarking a 'Lady Mussntmention collection'. He was clearly prone to exaggerate and, we might suspect, invent detail to make a good story, but the essence of his account of his dealings rings true, and it is easy to build up a picture of his regular customers, notably 'the American', who is the subject of this essay.

- Portrait of Mosheh Oved [Edward Good]

By Maurice Minkovski

Watercolour, 30 x 37.5 cm

signed and dated 1924

Ben Uri Gallery - The London Jewish Museum of Art

(founder of the museum)

He writes: 'At the beginning of 1920 I bought 300 old gem rings: Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Etruscan, Renaissance, and Eighteenth Century. I bought the whole lot for an absurd £600.

Many of them had crowned the collection of Signor Medina, an Italian Jew of the seventeenth century. Many of them had come from Lord Arundel's collection. Some were from the world-famous art collections of the First [sic] Duke of Marlborough; whilst others had belonged to the Polish national hero, Prince Ponitovski. A portion of them had come from other, doubtful sources.'

The gems were in 'the original red morocco leather ring-case, the original case which that great English artist, Sir Joshua Reynolds, had used as part of the background for his historical portrait of the First [sic] Duke of Marlborough.'

'Each of those rings bore a little note, on parchment thick as a slate, on which was inscribed its history and pedigree, as in a museum. And there was a catalogue to accompany it.'

The case was certainly authentic. It was one of ten made for the Fourth Duke of Marlborough (not the First, who was the soldier victor of Blenheim), and one is shown under the arm of his son in the Reynolds portrait which hangs in Blenheim Palace.

The Marlborough collection was the largest and best of the private collections of the eighteenth century. It was catalogued by Nevil Story-Maskelyne in the mid-nineteenth century, before being sold, first en bloc to a colliery magnate, David Bromilow, then piecemeal at Christies in London in 1899. It is possible that the 'catalogue' mentioned by Mosheh is the sale catalogue. Story-Maskelyne had made copies of all the pieces – sealing-wax impressions of the intaglios and electrotype casts of the cameos, with their mounts, and, as an expert in precious stones, his descriptions are reliable and he was not inexperienced in describing the iconography of the gems. His collection of these copies is in the possession of the Beazley Archive at Oxford, and have been the subject of a major publication which appeared in 2009 (J. Boardman, The Marlborough Gems, Oxford University Press). It proved possible, however, to discover the present whereabouts of only some 250 of the original 800 gems, and the search for the rest continues.

Clearly, many of the gems in Oved's box were Marlborough's. The Duke had, from Lord Bessborough's collection which he purchased, many of the Medina gems which had been sold in London, and a major part of his collection was the Arundel cabinet which was given him by his sister-in-law. The rest must have been from other sources, the 'Ponitovski' probably being some of the rich series of neo-classical stones made in Italy for Prince Poniatowski.

Oved was understandably excited, and he over-reacted:

'Nearly every gem ring was a valuable heirloom of antiquity, a choice specimen of the glyptic art, engraved by the skilful hands of great spirits. They had once graced palaces, museums, cabinets, and noble hands, no less than those brutal fingers which had left their nail-marks deeply embedded on the passing generations – marks which are still unhealed to this day.

Every separate ring had been a silent witness to more than one robbery, murder, and profitable transaction. More than once it had been drowned and washed up again by the sea, buried and exhumed, pledged and left unredeemed. More than one collector had stroked it gently and kissed it. More than one girl had sold herself for it, and more than one plagiarist had copied it – the ring and the girl.'

'I imagined myself selling the rings, one by one, and making three hundred poor folks happy for ever and ever, whilst I gained two or three thousand pounds on the transaction. I told myself that, with that money, I would issue a journal – a unique journal, in which the most expensive truths would be printed, on art paper. It would be sold at a penny a thick copy: illustrations, supplements and postage – free!'

Mosheh's dream was short-lived:

'As I was indulging in this dream an American came in, dressed in a dirty black straw hat, with the rest of his clothes to match. He saw the whole collection of rings and asked me the price of one which represented a nude Venus. I said it was £10, not thinking that he would buy it. He then asked how much I wanted for the whole lot. I said that I would sell it for £800, cash down.

'All right. It is mine.'

'All right. It is yours.'

'The next day the American came again, bought a Wedgwood plaque for £10, paid and said he had no more money. As he was speaking, a cheque fell out of the outer pocket of his overcoat. I picked it up and saw that it was an 'open' banker's cheque for £1,800. I handed it to him, at which he said: 'Oh, that is for an automobile. But I have no money for the ring collection.' It rather sounds as though he may have used cheques only for major purchases and otherwise travelled with pockets full of banknotes.

At this, Mosheh's business instincts took over. He pressed the gem box on him. 'Take it without money. Take it. You will pay another time. Only, please, take it with you now.' Then doubts set in about the foolishness of his action, reinforced by his wife's anger, but...'Next day, at about five o'clock, the American at last came in, now dressed like a hundred lords. He paid me and bought more, and more and more; suggested an excellent remedy for my poor blood circulation; and advised me to eat oranges every night. He gave me his good name and wealthy address, and bought more and still more. He put me on my feet, my golden feet.'

'Four years later the American came back, and he said to me: 'Do you know, Mr. Good, all the things I bought from you are still lying in the cellar, packed in the boxes, exactly as you sent them to me. I neither wanted them nor have the time to look at them. But if you could be so speculating and daring as to trust me with so much goods without knowing who or what I was, then you deserve all the business you have done. Do you still eat oranges every night?'

This seems to set the seal on the whereabouts of we know not how many Marlborough gems, still not identified. But the American returned often to London, and although Mosheh never reveals his name and address, the anecdotes accumulate, give a picture, and even yield clues.

He arrived again, before 1926, and 'instantly bought 'Little stones and bones', odds and ends, and ornate ornaments, articles ranging in value from a few shillings each to expensive ones right to big numbers of pounds'; 'He bought and threw the things into his pockets, without ceremony, without tissue-paper, without cotton-wool, and without boxes, not as done by careful people of all classes, who take care to remain in their specific classes.' And he talked freely, telling Mosheh to give up smoking, drink five glasses of water in the morning and eat oranges at night.

'How much is this cameo?'

'Fifty pounds.'

'This would have cost a hundred in Paris. No? What's the lowest?'

'Forty five pounds,'

'Didn't you say forty pounds.'

'All right. Let it be forty.'

He gave it a fling into his pocket so hard that the miniature's nose positively bled.'

Then he spotted the Marquis of Breadalbane's silver and gold lamp set with 114 Poniatowski intaglios and bought it for £600. The body of the lamp re-emerged on the New York and London markets recently, with no record of recent owners but once in the hands of a South American dealer. Another cameo the American bought was addressed to go to San Francisco and 'in the meantime, he telephoned to ask if they had yet found oil for him in Florida. How much dividend his stocks were paying this year in Canada he wanted to know; also why the national bank of Italy was not paying him out; and if his good lady would be at the Hyde Park Hotel at one minute to one. As I was looking at this gifted poet of reality I thought within myself: 'For your sake alone, it is worth while that the Sodom of exploitation should not be destroyed.'

- The Breadalbane Vase/Candelabrum

(engraving from The Illustrated Art Journal Catalogue of the International Exhibition of 1862, 218).

He made a great fuss of his physical fitness, stripped off to show Mosheh his muscles 'like a Greek figure of Hercules in the attic of an antiquarian'.

'See, I am a director of a hundred companies. I help Europe. How? Listen attentively.

I myself, when I was thirty years of age, sold newspapers in the streets, I was like every other beggarly idler, like all those other scamps and beggars you see riding on the cheap buses. One day I took myself in hand and said to myself: 'Be a man, or perish!' 'The great doctors of Vienna and Winnipeg say that I am certain to live to a hundred and thirty-five years of age. You, too, can become like that. Only, will, will!' ' I will not any more be tolerably good, I want to be great. Oh, I want to be great!' At this point the American became for Mosheh 'Superman'.

Superman 'came over regularly every year, calling for days at a time at 'Cameo Corner', and revivified business with transfusions of his rich gold'. 'One fine summer morning in 1933 the superman arrived from the seething New World into the lukewarm Old World, and made straight for my shop'. He had become, it seems, obsessed with the beauty of 'Princess Sanitah', the sculptor Epstein's model. Is she 'a reality or a fantasy'? Mosheh was dubious – 'He is on the dangerous verge of seventy, and she is on the perilous verge of poverty'. But he arranged a meeting, and Superman fell in love, wanted to install her in a London mansion to promote Beauty, with his invention of a comb which pulls the hair back from the forehead to remove the wrinkles: 'Buy a comb, your beauty to renew, And look the image of twenty-two'. She scorned him, 'blew a smoke-ring high into the air, shaking her head.' 'What a smoking devil! A skinny rabbit! And that's what you call beautiful! Come to America, and I will show you lovely women, peaches every one. In America they wouldn't give a nickel for a witch like that!'.

Superman 'came over regularly every year, calling for days at a time at 'Cameo Corner', and revivified business with transfusions of his rich gold'. 'One fine summer morning in 1933 the superman arrived from the seething New World into the lukewarm Old World, and made straight for my shop'. He had become, it seems, obsessed with the beauty of 'Princess Sanitah', the sculptor Epstein's model. Is she 'a reality or a fantasy'? Mosheh was dubious – 'He is on the dangerous verge of seventy, and she is on the perilous verge of poverty'. But he arranged a meeting, and Superman fell in love, wanted to install her in a London mansion to promote Beauty, with his invention of a comb which pulls the hair back from the forehead to remove the wrinkles: 'Buy a comb, your beauty to renew, And look the image of twenty-two'. She scorned him, 'blew a smoke-ring high into the air, shaking her head.' 'What a smoking devil! A skinny rabbit! And that's what you call beautiful! Come to America, and I will show you lovely women, peaches every one. In America they wouldn't give a nickel for a witch like that!'.

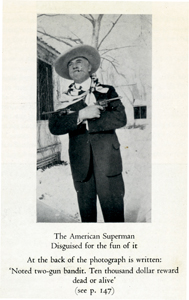

That is all we learn of the American from Mosheh Oved – that he visited England and Europe regularly from 1920 on, stayed at the Hyde Park Hotel, that he bought a box containing Marlborough gems and an automobile in 1920, that in 1933 he seemed on the verge of seventy, the photograph, and that he had various business connections (Florida oil, railroads, a San Francisco address, businesses in Canada). What he or Mosheh concealed we can but guess.

The American Superman is worth identifying for many reasons – new insights into his behaviour and manners, and for us the possibility of finding the Marlborough gems that he had bought.

The possibility of finding Superman's box is therefore a matter of some concern and importance. The original Marlborough Collection comprised classical gems from the last centuries BC and early AD, many Renaissance pieces, as well as later, neo-classical, all often in elaborate jewelled mounts, but mostly set in rings. A major part was the Arundel Collection which comprised gems collected by the Gonzaga Dukes of Mantua in the 15h/16th centuries; the 18th-century Bessborough Collection including purchases from the Medina Collection and the collection of Philip Stanope; and pieces collected by the Duke himself in Italy and elsewhere, as well as neo-classical works, since he was also a patron of British engravers.

So, can we identify Mosheh's 'Superman' and locate more of the Marlborough gems? There are few material clues but the manner of the first purchase evoked in an American colleague, Carol Mattusch, recollection of the record of an episode in Naples in 1925. It concerned the Chiurazzi factory which made high quality bronze copies of ancient sculptures. With her colleague Damiele Struppa she had interviewed Elio Chiurazzi in 1998, and this is the transcript of Daniele's notes about one of the episodes recounted, which I am kindly allowed to copy here, an episode 'probably occurring between 1920 and 1925':

'A shabbily dressed man visited the shop and chose a large number of exceedingly beautiful and expensive pieces, for an amount of several million liras. He signed the check, and asked that the statues be packaged and sent to his yacht in Taormina. The cost of the entire operation was huge and Chiurazzi was concerned that the check might turn out to be bad. So, he went to talk to the Director of the Banco di Napoli for advice. The Director told him to take some time, so that he could in the meantime send a cablogram to the bank, to verify the credibility of the buyer. After a week the Director called him and told him. 'Don Federico, you can package your bronzes and send them right away'. He then shared the cablogram he had received in reply to his request. It said: 'John Ringling, uomo buono per qualsalsi ammontare. Trae dalla sua stessa banca'. – John Ringling, a man good for any amount of money.

John Ringling was the most prominent of the Ringling brothers who managed Barnum and Bailey's Circus, bought by them in 1907, through the first half of the twentieth century. He was a multimillionaire, benefactor of Sarasota, Florida, where he lived, and founder of the Ringling Museum there. He was born in 1866 and died in 1936, aged 70. There are good sources for his life and collecting in D.C. Weeks, Ringling. The Florida Years 1911-1936 (1993) and in the 1996 Exhibition Catalogue of the Ringling Museum, called J.R. Ringling, Dreamer, Builder, Collector. His nephews had a very vivid memory of Uncle John, expressed in The Circus Kings (by Henry Ringling North and Alden Hatch, New York, 1960). The Ringling Museum has the Chiurazzi bronzes, and indeed a fine collection of gemstones. Sadly, they are not ours, but the search is on, and the Ringling story has enough in it to guarantee, I think, the identity of Mosheh's Superman.

The dates fit exactly. Ringling was 56 when he first visited Mosheh; in 1933 Mosheh says Superman was 'on the dangerous verge of seventy' (Mosheh, 264) when Ringling was 67. In 1920 we are told that he bought his first Rolls Royce, an old car that had been owned by the last empress of Russia (Weeks, 68; Circus Kings 231). And it was in 1920 that Mosheh saw his American's cheque for £1800, 'to buy an automobile'. He was the proud possessor of a yacht. Ringling and his wife Mable toured Europe annually in the 1920s: their 'traditional summer journey across Europe' (Weeks, 183).

- The mystery millionaire and Ringling

[View larger image]

The appearance fits. There is the shabby appearance both in London and Naples, belying his status as a millionaire. There is also the behaviour. ‘Part of his method [of buying] was to conceal his knowledge behind a bucolic manner’ was the comment of Ringling’s nephew, in an account of the circus family which dwells much on his favourite Uncle John (Circus Kings 135). The photograph matches closely the physique and features of Ringling – the stocky but tall figure, 6' 1” high, the jowls, the shape of the heavy eyebrows, the shape of the ear (an important identifier which had been used before fingerprints), the white-hair sideboard (see Weeks, 15, fig., where it is grey in 1929; he must have dyed his hair usually), the set of the head (he is pulling a face in the photograph). He took hours to dress ‘with what mysteries of toiletry....that took so long’ (Circus Kings 203). He is easily imagined as 'With a very red face, a gold watch chain across his prosperous stomach' (Weeks, 157). He may have encouraged Mosheh not to smoke but Ringling is smoking in the photograph and was known as a cigar man, and he was proud of his physique (Weeks, 16) without necessarily being a health-freak.

The contradictory aspects of Superman's character, revealed by Mosheh, are closely echoed in Ringling. 'In the 1920s, Ringling had two public images, the capitalist entrepreneur, and the circus man who lived like a king' (Weeks, 167). He started life as part of a family concert show, at five being dressed as a clown ‘Billy Rainbow’ and ‘worked like a veteran’ (Circus Kings 56-7). At twelve he ran away for a while to start his own business (ibid., 62), and at fifteen he dressed as a Dutch clown (ibid., 68, and picture), and it seems that he never quite lived down his rougher early days. In Sarasota he was the millionaire benefactor, and tried to behave as such acquiring the necessary social polish, but he was a ruthless businessman and was clearly at pains to disguise where he could the other aspects of his life, although he was ‘still and forever a wonderful clown’ (ibid., 202). He was interested in Florida oil and its railroads (ibid., 138-9), an interest commented on by Mosheh. He was lucky in his first wife, Mable, and 'Within their home he put aside the coarse language, the flaws in character that marred his circus and business image, and the haughty facade that he presented to the world' (Weeks, 255). ‘Not that he was completely faithful to her...Aunt Mable realized that her husband was too old and gay a dog to learn new tricks of behaviour. She treated his infidelities as though they had never happened (Circus Kings 163). Clearly, during his annual trips through Europe, he sometimes reverted to type in a way impossible for him in Florida.

Ringling's collecting career also suits the identification. It seems that he started collecting, especially from auctions and dealers, early in the century and until the 1920s his interests were very haphazard. He soon came to regret them, and it may be that 1920 was near the end of this first phase of his collecting career. 'They made purchases here and there, but with no particular purpose or knowledge, and they travelled in Europe each summer' (Weeks, 168). At any rate he decided that he had been too haphazard and began to discard much that he had acquired. 'There was at least one accumulation of artworks predating the Museum collection. Ringling was apparently unsatisfied with the result, however, and sold the lot. The contents and location of this initial effort are unknown' (Dreamer, 56). From 1924 on he started again, more seriously and guided by the connoisseur Böhler, and with the clear aim both to furnish his new home, which was to be like a Venetian palace (Ca d'Zan: Weeks, 112-28), and to stock the Ringling Museum in Sarasota. The Chiurazzi bronzes were destined for his building of a new Ritz Carlton Hotel for Sarasota, but eventually came to the Museum.

It is possible that the box of rings was regarded as a casual purchase of no real importance and so discarded at an early date without further inspection of its contents, which at the time meant nothing to him. In that case they have been 'somewhere else', for some eighty years. Or it was kept unopened with other effects and could still lurk among the debris of his estate, unrecognised. 'Many art objects that came from auctions and sales remained undisturbed in their cartons and crates, never opened until the estate appraisers examined them' (Weeks, 274-5). There must be hope still. That the collection has not been dispersed already seems indicated by the fact that it included among the Marlbororough gems some labelled 'Medina'. Of Marlborough’s Medina gems only 18 out of 37 have resurfaced and it is not easy to judge whether any of these could have been in London in 1920. One was a nude Venus cameo, the only single Venus study in the whole Marlborough collection, and might be the one that the American noticed and offered £10 for, but we cannot be sure that this was the Medina one, nor can we trace its history between 1899 and 2005 when it re-emerged at Sothebys. It is possible too that the case and its contents was put together by the dealer Whelan from various sources, but we do not know for whom. We do know he had some of the original red cases.

We surely have the man; but not the gems, as yet.