The Marlborough Gems

April 2008. Ioannou School for Classical and Byzantine Studies, Oxford.

What I want to describe to you is a research project of the Beazley Archive upstairs, which has run for some years now, the goal of which was a book for the Press, now delivered. It has a local appeal since it deals with a collection of some 800 gems, ancient to 18th-century, once at Blenheim Palace, sold piecemeal in 1899, and which we have been reassembling at least in paper or in facsimile.

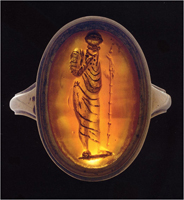

First, some of you may need to be told what the gems are. They are hard semi-precious stones which have been cut with intaglio figures and designs so that they can be set, usually in finger rings, and used as seals if you press them into sealing wax or clay. And beside them the more familiar cameos, which are much the same thing but with the figures cut in relief on layered stones, usually so that they appear light on a dark background. The other important thing to remember is that they are all extremely small, many no more than one inch in length, few as big as two or three inches. So do not be deceived by the size of the images on the screen. They are, moreover, often set in expensive and exquisite jewellery mounts or rings. So this is going to be an exercise in admiration of the miniature, but also, importantly, of the habits of collecting such glamorous objects over many centuries, so it is also about the reception and influence of classicising arts down to the 18th century.

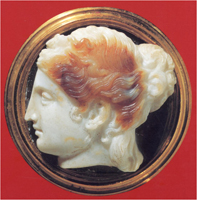

This miniaturist art has been practised in the western world from antiquity to the present day. It figures in collections, private and public, and, however disgraceful you might think it, it also attracts the rich, public or private. For instance, here is one [left] It is a sardonyx cameo showing the bust of the Roman Emperor Claudius (or Caligula), just three inches high, quite a big one in fact, sold in New York 2 years ago for $321,100. And there are others of the collection which would go into seven figures if they ever came to the market.

This miniaturist art has been practised in the western world from antiquity to the present day. It figures in collections, private and public, and, however disgraceful you might think it, it also attracts the rich, public or private. For instance, here is one [left] It is a sardonyx cameo showing the bust of the Roman Emperor Claudius (or Caligula), just three inches high, quite a big one in fact, sold in New York 2 years ago for $321,100. And there are others of the collection which would go into seven figures if they ever came to the market.

The collection was made by the 4th Duke of Marlborough in the second half of the 18th century, 250 years ago.

Here he is in the portrait by Joshua Reynolds [right], and in his hand he holds an ancient cameo, while his son holds one of the ten red-morocco bound boxes which held the rest of the gems - a collection which the Duke kept in his bedroom and resorted to as a relief from his ambitious wife, his busy sister and his many children. What he holds in his hand is a cameo of the emperor Augustus, now in Cologne.

Our aristocracy was always hard up, either through extravagance or the demands of offices of state, and until the Dukes of Marlborough hit on the idea of marrying American heiresses, they had to dispose of their assets. The gem collection was sold, first as a whole in 1875, then as separate pieces in 1899, and so it was dispersed into the hands of collectors, museums and, especially, dealers. Of the 800 gems, we know the present whereabout of less than 250, yet we know what virtually all the others look like. This is possible thanks to the zeal of Professor Story-Maskelyne, a mineralogist, who made a catalogue of the collection in the 19th century, but who also made sealing-wax impressions and electrotype casts of all the stones - an archive which is now housed in the Beazley Archive upstairs.

This [below - far left] is the sort of thing - an electrotype metal copy/cast of a cameo, one of an intaglio, and two sealing wax impressions. So it is possible now to catalogue and study in illustrations the whole collection - and this has been our task, with help, over the last years. And lest you think mere stones might be as boring as coins, I should add that the best of them, especially in the renaissance, were set in real jewelled mounts and rings, with elaborate modelled figures in miniature and a lot of colour from enamel. Here [below middle left] is an example, and it looks as good from the front [below middle]. Here is another [below middle right] with a beautifully painted back to a Renaissance study of a baby-cum-eros-cum-Horus with a cornucopia [below far right]. Apart from the intrinsic beauty of some of the stones, onyxes and sapphires among them, this is by no means a colourless subject.

The history of the collecting is an exciting one - it involves Italian Renaissance princes of Mantua, who included some of the most colourful and resourceful figures of 15th and 16th century Europe, such as Isabella d'Este and the Gonzaga princes - eventually disposing of parts of their family collections before their city was sacked in 1630; it involves European dealers and English royalty, not least Prince Henry [below left] who might have been our Henry IX had he lived; and a shrewd and wealthy collector, the Duke of Arundel, [below right] here in a portrait by his friend Rubens and in the Ashmolean which houses many of Arundel's ancient marbles. And there were various noblemen of the later 17th and 18th century as well as Italian collectors and dealers; and finally the patronage by our 4th Duke of Marlborough of English gem-engravers working in the neo-classical manner.

We start with the earliest of the collectors. Lord Arundel started collecting in the early 17th century, the time of James I, Charles I, then of Cromwell. He collected largely thanks to the wealth of his wife, and mainly in the eastern Mediterranean, Turkey and Greece, then in Italy, and mainly books and statues. There is a good display of the Arundel marbles in Oxford, or will be, we must hope. His first gems were, one of them, a gift from his friend Prince Henry, [below left] which had come from an old Dutch collection and is now secreted in Belvoir Castle, where I stole this photograph. It has busts of Augustus and Livia, in silver relief on one side, intaglio on the other. And another from his friend the artist Rubens [below right], which is perhaps the most famous in the collection - now in Boston and showing a scene involving Cupid and Psyche in what is probably an initiation ceremony of some complexity. I shall come back to this later.

The Mantuans had been selling off their pictures - oil paintings by Titian, Giulio Romano, Raphael, Mantegna and other leading Renaissance artists - a great many of them bought by Charles I of England. He was also offered the gem collection but thought it too expensive, so Arundel snapped it up, to add to his pieces from Prince Henry, and this cameo from Rubens, and a cameo owned by Arundel's own saintly mother, Anne Dacre [below]. We have been able to recognise this from a portrait of her recently on the market in London, and although we do not know where the original cameo is we do know what it looked like from the 19th-century photo *** and an electrotype. It shows an Assumption of the Virgin Mary with angel heads around her.

You can see that the chase for these gems can be more than simple library work and museum-hunting, and it has led me and my colleagues from Malibu to Monaco and, on paper atleast, from Bari to Japan. In the States the main owners are Boston, about a hundred in Baltimore, which is the most anywhere, and a few now in Malibu at the Getty, two in Chicago, one at Atlanta. There are several in our BM and V&A, and in private hands here and in Europe. And there are many more yet to be located; this is one of the objects of our exercise in the Beazley Archive. And we have put on line pictures of those we still seek. And just to show that this was not a waste of time, only last month a collector in Germany revealed that she had bought in recent years one of our gems, not recognized as such until she saw it on the web like this [below left]. A cameo of a lusty Renaissance Venus holding Mars' spear for him [ below middle] and with its ornate back [below right].

But let us look at more of the Arundel gems from Mantua and at the taste of the Renaissance collectors:

The Gonzagas fancied themselves as heirs to the Roman Empire and encouraged the making of pictures and gems which celebrated the famous deeds of ancient Romans - so, in a way, did we in Britain pre-war, when I was a schoolboy and we were read Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome - 'How Horatius held the bridge in the brave days of old'. The Renaissance liked such stories and Horatius himself appears on some of their gems – [right] here is the electrotype copy of one that Arundel got - Horatius stands on the bridge fighting off the Latins, while behind him fellow Romans are destroying the bridge he stands on. The River Tiber waits for him to jump in - to escape eventually, when 'even the ranks of Tuscany could scarce forbear to cheer'.

The Gonzagas fancied themselves as heirs to the Roman Empire and encouraged the making of pictures and gems which celebrated the famous deeds of ancient Romans - so, in a way, did we in Britain pre-war, when I was a schoolboy and we were read Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome - 'How Horatius held the bridge in the brave days of old'. The Renaissance liked such stories and Horatius himself appears on some of their gems – [right] here is the electrotype copy of one that Arundel got - Horatius stands on the bridge fighting off the Latins, while behind him fellow Romans are destroying the bridge he stands on. The River Tiber waits for him to jump in - to escape eventually, when 'even the ranks of Tuscany could scarce forbear to cheer'.

But there were many serious views of the classical gods and occasions to be found, often in original.

Here [below] is the goddess Demeter receiving a gift of corn from the hero Triptolemos. The cameo had once belonged to the Medici family, one of whom must have given it to a Gonzaga in Mantua for it to turn up in Arundel's collection. And it is now in a private collection in London - we found it two years ago.

No less to their liking, and echoing their way of life, were scenes of drinking - with Bacchus and satyrs, or of Venus and Cupid. There were several surviving from antiquity for them to collect, and often copy, Here [below left] is a cameo with little Cupids at worship. And this is a finer one [below middle] with cupids building a trophy. From the Bacchic side there are studies of bacchants, wild women serving the god, often with their hair flowing and dancing in ecstasy, or more sober like this [below right]. Some of these are or copy good Hellenistic originals.

Another favourite subject of the early Roman empire was the life of the sea gods.

Here [below left] is one where Renaissance owners thought they might see Antony and Cleopatra at one of their seaside revels, but in fact it is the Greek god Triton with a sea nymph, and a complicated group much favoured for sculpture and for jewellery - and this is just for a small finger ring. You can perhaps see the design better in impression [below right].

One big problem is that Italian Renaissance artists were as good at gem emgraving as any ancient Greek or Roman, with the same materials and techniques. They were expert both at copying but also at creating original and plausible classical compositions. We are sometimes at a loss to know whether what we are looking at belongs to the 1st or the 15th century AD, a sad confession for any art-historian.

Divine and heroic subjects were simply asking for new treatment even when they had not been treated in the same way by antiquity. Here [below] is the impression of a Renaissance gem showing the forge of the god Vulcan with his men working at armour; it is the sort of subject you see also on Renaissance silver and in paintings.

Renaissance artists were good at composing classical scenes and groups in the antique manner but of subjects which have no ancient authority in art. Various groups of gods and goddesses were popular [below left] and on gems they are often seen to be light adaptations of groups composed by artists in other media, usually painting. So, there may be a Raphael background to this one. Big battle scenes [below middle] with the Roman army prominent and its SPQR banners [below right] are another favourite for compositions with rather more figures than any ancient engraver would have tolerated or attempted.

More remarkable, [below] this shell cameo showing the death of the hero Meleager - swarming with 27 tiny figures, and the cameo less than one and a half inches long. This was a rather special jewellery type, more favoured in the north of Italy and Renaissance Germany. Mantua was in the north and for long under the sway of the Hapsburgs beyond the mountains.

Portraits of famous Romans were popular, therefore ancient ones were collected and they were also copied from coins or medals. They bolstered the esteem of Renaissance princes who saw themselves as successors to the glories of the Roman Empire.

The emperor Claudius shown as Jupiter [below] is a good ancient example that antiquity favoured, and Renaissance princes too could think themselves assimilated to ancient gods, heroes and emperors. I show this in electrotype, which often shows more of the detail than the semi-translucent stone; the original is in Chicago where it has been given a new mount.

Some are of prominent civilians, like the orator Cicero [below left], here in a plaster impression, [below right] here in original, not all that easy to see even with the lght coming from behind the stone, which is not the way it would have been mounted in antiquity. More are of the imperial family whose emperors tend to look rather alike and were copied often for propaganda purposes in antiquity, and then in the Renaissance.

And who could fail to be inspired by the noble original Roman features of this consul [below]. We have yet to find it.

Best are the gods, imperial empresses and princesses of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD: Apollo [below left]. Agrippina [below right], with their elaborate hair-dos.

You can guess [below] how difficult it is to photograph a transparent stone like this.

Identities are important too, this [below left] certainly derives from a classical pairing of the heads of Dionysos and a satyr, a well known ancient motif, but was identified as Socrates and Plato [below right].

A beautiful pair of ancient engraved plaques include one [below left] showing the young Augustus as the god Hermes, and the other his sister Octavia as Diana [below right]. The Duke got both pieces, one from the Arundel collection, the other by purchase. They have met each other again at last in the British Museum and may look a pair but in fact they are not.

And here a no less accomplished cameo of a youth and girl [below] - maybe Venus and Adonis - but who knows what identity was in the mind of the late Renaissance engraver whose skills could so readily match those of classical antiquity.

But if you want Renaissance invention and vigour, [below] how about this - a sealing wax impression of a gem in Baltimore. At the right Bacchus is arriving in his chariot, to pick up Ariadne, who is standing at the seashore watching the boat of Theseus, who has dumped her, sail away home. All right, Titian did it better, but on a large canvas - this is barely more than an inch wide.

So far I have shown you only those gems that came from the Renaissance collection, ancient and not. Here is just one more of the most famous pieces, with a pedigree that goes back to the early 15th century, but was almost certainly made in Rome in the 1st century AD. It is the so-called Felix gem - now in the Ashmolean [left]. 'Felix' because it is signed by the artist Felix, also named in an inscription found in Rome. The stone is a dark agate, very thin and finely engraved, just one and a half inches wide. It is an unusually complicated piece of narrative. The walls are the walls of Troy, with outside them a statue of Poseidon on a column, a feature noticed by the painter Mantegna in Mantua and used by him in one of his Roman paintings. Below, Diomedes is escaping from Troy holding the Palladion statue of Athena which he has stolen, and he is greeted by Odysseus, who has slain one of the Trojan guards or priests, whose feet we see. This is the most detailed treatment of the subject to have survived - most other examples just have the single figures, and the original was perhaps of two medallions, maybe 4th-century in date, which Felix much later put together in a single composition – [right] here is another Arundel gem just of the Diomedes with the Palladium, but this is certainly a Renaissance copy.

So far I have shown you only those gems that came from the Renaissance collection, ancient and not. Here is just one more of the most famous pieces, with a pedigree that goes back to the early 15th century, but was almost certainly made in Rome in the 1st century AD. It is the so-called Felix gem - now in the Ashmolean [left]. 'Felix' because it is signed by the artist Felix, also named in an inscription found in Rome. The stone is a dark agate, very thin and finely engraved, just one and a half inches wide. It is an unusually complicated piece of narrative. The walls are the walls of Troy, with outside them a statue of Poseidon on a column, a feature noticed by the painter Mantegna in Mantua and used by him in one of his Roman paintings. Below, Diomedes is escaping from Troy holding the Palladion statue of Athena which he has stolen, and he is greeted by Odysseus, who has slain one of the Trojan guards or priests, whose feet we see. This is the most detailed treatment of the subject to have survived - most other examples just have the single figures, and the original was perhaps of two medallions, maybe 4th-century in date, which Felix much later put together in a single composition – [right] here is another Arundel gem just of the Diomedes with the Palladium, but this is certainly a Renaissance copy.

Arundel had a mixed career. He changed his religion twice, from Catholic to Protestant, and back again, spent a while imprisoned in the Tower of London, and under Cromwell retired to exile in Italy, at Padua, taking his gems with him. There he died in 1646, his body returned to England, but his heart and entrails left behind in the cathedral of Padua [left], marked by a plaque [right] referring to his innards - 'interiora'. This is a photo by Claudia Wagner, as are many of the others I show you; she works in the Archive and is a key figure in the project.

Arundel had a mixed career. He changed his religion twice, from Catholic to Protestant, and back again, spent a while imprisoned in the Tower of London, and under Cromwell retired to exile in Italy, at Padua, taking his gems with him. There he died in 1646, his body returned to England, but his heart and entrails left behind in the cathedral of Padua [left], marked by a plaque [right] referring to his innards - 'interiora'. This is a photo by Claudia Wagner, as are many of the others I show you; she works in the Archive and is a key figure in the project.

Arundel's collection went back to England in its fine painted Flemish cabinet, which we have yet to find again though it survived at Blenheim [left] into the 19th century. The gems passed through various hands, including once being pawned for £1500, until it reached a young woman who was to be the 4th Duke of Marlborough's sister-in-law, and who gave them to him.

Arundel's collection went back to England in its fine painted Flemish cabinet, which we have yet to find again though it survived at Blenheim [left] into the 19th century. The gems passed through various hands, including once being pawned for £1500, until it reached a young woman who was to be the 4th Duke of Marlborough's sister-in-law, and who gave them to him.

The Duke himself was the grandson of the First Duke, John Churchill, the victor of the battle of Blenheim, which gives its name to his palace, which we all know. He had started his collecting already, on tour in Italy. There, the collector and dealer Zanetti had a prime collection and after long bargaining he gave up to our Duke his prize piece. It is a portrait of the Emperor Hadrian's favourite, Antinoos [right], and generally regarded as one of the finest portrait gems from antiquity. It had been broken, and restored in a gold mount, as you see; and it has at a break a rather unhelpful inscription. It is in a strange black stone and was so popular and admired that it was copied several times by artists, in Italy and then in England once it got to Blenheim Palace. We had the pleasure of handling it last year in a private collection in Monaco.

Another of Zanetti's gems got by the Duke was a portrait of Sabina, [left] wife of the emperor Hadrian. Back home our Duke was able to buy the collection of Lord Bessborough, which was itself composed of gems from an Italian collection, once in Livorno, but then sold in London, and the gems collected in Italy by Lord Chesterfield's young brother, Philip Stanhope. This was the age of the Grand Tour when noblemen and others travelled Italy and brought back relics of the classical world for their country houses, usually statues, but also coins and gems, and if they could not afford them, at least collections of glass or plaster casts of the gems, in which there was a roaring trade. Lord Chesterfield himself was rather against too much collecting of trivia and warned his own son in Rome 'no piping or fiddling, I beseech you; no days lost in poring upon imperceptible intaglios and cameos'. A leading collector and dealer in Rome at the time was Baron Stosch, [right] seen here with some of his cronies. He was busy, unscrupulous, and in his spare time a spy for England in Italy.

Another of Zanetti's gems got by the Duke was a portrait of Sabina, [left] wife of the emperor Hadrian. Back home our Duke was able to buy the collection of Lord Bessborough, which was itself composed of gems from an Italian collection, once in Livorno, but then sold in London, and the gems collected in Italy by Lord Chesterfield's young brother, Philip Stanhope. This was the age of the Grand Tour when noblemen and others travelled Italy and brought back relics of the classical world for their country houses, usually statues, but also coins and gems, and if they could not afford them, at least collections of glass or plaster casts of the gems, in which there was a roaring trade. Lord Chesterfield himself was rather against too much collecting of trivia and warned his own son in Rome 'no piping or fiddling, I beseech you; no days lost in poring upon imperceptible intaglios and cameos'. A leading collector and dealer in Rome at the time was Baron Stosch, [right] seen here with some of his cronies. He was busy, unscrupulous, and in his spare time a spy for England in Italy.

Apart from the Zanetti gems the Duke acquired from Bessborough and others many pieces which could even match the Arundel collection, to which they were added. I shall show you a selection, repeating many of the motifs we saw in the Arundel gems, but with a wider range both of antiquity and from the later production in the 17th and 18th century.

The Duke's collection had nearly doubled by his death in 1817. It reflected much the same taste as did the Renaissance princes but with a more scholarly element, encouraged in this case by the Duke's tutor, Jacob Bryant, who was modern enough to write a book holding that the Trojan War never happened. They went for imperial subjects such as were naturally sought out in all periods. Here [below left] is an unusual one in an unusual material - turquoise, showing the empress Livia holding a bust portrait of Augustus. It is not complete, and we now only guess at how it looked when it had been set in its Renaissance mount of gold and enamel, of which we have only the cast and a 19th-century photo [below right].

Here is a fine portrait of Tiberius' stepfather Augustus [below left] in its splendid 18th-century mount. We rediscovered this last year in a private collection. And to round off the imperial family, here is his great-uncle Julius Caesar [below right], on a Marlborough gem in Baltimore.

This [below left] is a good example of a real problem piece. A big cameo now in the BM, probably a pair of deities rather than imperial portraits though there have been various identifications, not least those inscribed in the wreathes at the top corners of the mount. In the mid-19th century the mount, which was added in the early 17th century since it was illustrated by Cassiano del Pozzo, as described as gile silver. What there is now in the BM is a copy in brass, from which the inscriptions in the wreathes have been reased. It looks as though, between the ales of the gems, Mr bromilow decided a copy would do, and he also removed a good restoration of the man's shoulder. [below middle] Luckily, though, he did a good job of copying the back too, which carried a new inscription of the early 18th century [below right] saying that the piece had belonged to the Dukes of Sannesi, then to Portuguese, Duke de Fuentes.

The heroic subjects were always popular, and none more so than those involving Hercules, and not always at his best - here he is drunk [below left]. Here, in a gem which had been bought back by someone to leave in Blenheim as a memento of the great collection, [below right] he is peeing.

We are used to seeing him wrestling with the lion [below left], but how often have you also seen the lion's cave, below here, and his lioness wife and a cub inside it? And here [below right] in a fine cameo trundling along accompanied by two cupids clinging to him. This is ancient.

More conventionally a fine bust portrait of him here [below left], a cameo once in the possession of Pope Clement VII, and on its back [below right] a bust of his lover, that is Hercules' not the Pope's, Omphale, dressed in his lionskin, or just as possibly young Hercules himself.

Of a more decorative nature are the many Medusa heads, the horrifically beautiful face ringed with snakes [below left] here on an elaborate finger ring in the V&A. She appears more often in cameo – [below right] here a really large one which might have been set on an emperor's corselet. We only recently found it in Liverpool. Its back has Christian crosses and motto on it so it had survived long above ground.

Another highly decorative subject was the Bacchant or maenad in her wild dance for Dionysos; there are many studies of her head and shoulder, mainly ancient cameos, and here [below left] is one of the best. Back in the 19th century it had a mount like this [below right].

Here is the goddess Diana [below left], not an ancient gem this time, and I show it because it is an example of a stone with another device on its back, which is not uncommon and was rather favoured in the Renaissance. On the back of this one [below middle] there is a rather decadent looking Venus and Cupid. Venus looked more at home here [below right] in the wax impression of a still-lost Renaissance gem showing her riding in a chariot shaped like a shell, with Cupid up behind, and pulled by a pair of doves.

Not all the heroic scenes make immediate sense. Here [below left] what might be Apollo looks down at a seated woman beside a shield, and above there is a crow. The crow might indicate the woman whose name would then be Coronis - meaning crow - but what is she doing with a shield and there are versions which have her wounded too. You see it [below right] better in electrotype, and this is another we have yet to find to fully understand.

We looked at some historical subjects, and at the Felix gem with its scene of Troy. Here [below] is another one, where Apollo is stopping Achilles from pursuing Hector within the walls of Troy, as described in the Iliad. Our Arthur Evans once had the ancient cameo version of this one, also in the collection.

Reflections of history through myth or symbol was not unknown to antiquity. Here a fine cameo [below] of an elehant trampling on a fish. One is reminded of coins with an elephant, a symbol for Caesar, facing a carnyx, the serpent-shaped war trumpet of the Celts, and may speculate upon the circumstances in which the combination with a fish was deemed significant in Caesar's time.

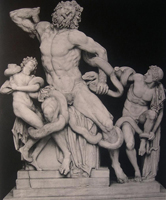

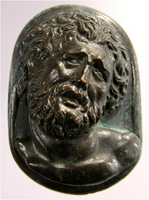

Ancient statues were much prized by aristocracy on the Grand Tour, who brought back many for their country houses. To help, engravers made gem copies of many of them. A favourite sight in Rome was, of course, was the Laocoon group [below left], and here is a cameo copy of the head of the old father [below middle]. But a more original artist of the 16th century, not long after the original was found, made a special version [below right] in shell, copying the outlines of the old group, but turning the children attacked by the snakes into babies, and adding one below.

This cameo [below left] is in New York. It shows a nymph suckling a baby panther - odd behaviour but not without parallel - recently in a Rangoon zoo a woman suckled two baby tigers who had lost their mother. It echoes the stories of human babies being suckled by wild animals. This version is rather over-elaborate with a flower garden in the middle, a satyr holding the panther's tail, and a lot of paraphernalia. It must be a Renaissance version of an ancient composition, known to the artist perhaps in another cameo – [below right] like this original and far finer fragment of the same scene, reversed, now in a private collection in Germany.

The Duke was a patron of various 18th century gem engravers in Britain, and he encouraged them to copy the stones he had, as well as other classical subjects. There was a fine Eros statue in Rome, much copied. Here [below left] is the Rome Eros Centocello head as copied for him by the engraver Nathaniel Marchant. And another of his protegés, Edward Burch, [below right] made for him a copy of the famous Antinoos we have seen already. Thus, the Duke's collection of old gems was proving an inspiration for engravers of the 18th century, and there are present-day engravers with the same motivation.

Animals were a good subject, domestic, wild and mythical. Here is one of the finest – [below left] the head of the dog star Sirius set in a finger ring. The rays around its head show it is a star, and on its collar we read the name of its engraver. But the head is so deep cut into the stone that it is virtually in the round - a tour de force. You get some idea of its energy when it is brightly lit from behind, as it probably never was in antiquity [below middle]. The 18th-century drawing [below right] shows how deeply it was cut.

The animals were especially popular subjects for ancient and later cameos. Here [below far left] is a fine lion; here [below left] more unusually and for a finger ring engraving, a spider in its web. A beautiful leopard cut in an appropriately mottled stone had been owned by Zanetti and our Duke wanted it but the Italian sold it to the Duke's cousin at Althorp. [below right] Here it is, now in private hands in London, and from it we can see that our Duke had it copied for himself, also in a mottled stone, we are told, but it was differently set and we have of it only the cast [below far right].

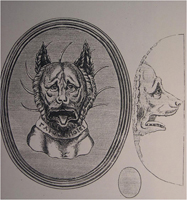

Theatrical masks were another good subject - here [below left] one of a satyr with a blind eye; another [89] a more unusual grotesque; and a whole comic actor [below right], recently sold in London.

Modern portraits too, folk like Philp II of Spain, even Cromwell, and [below] Mary Queen of Scots.

Finally, what might be regarded as the prize piece - certainly the one most talked about and copied and yet something of a mystery still. It is a cameo now in Boston [right], and the subject is generally called the Marriage of Cupid and Psyche, which, for a start, is almost certainly wrong. I suppose it was made somewhere in the 1st century AD, not too early, although a case could be made that it is in fact a Renaissance work - but I do not want to confuse you. At the centre we see a chubby little Cupid clutching a dove beside an equally diminutive Psyche with butterfly wings - his love and a personification of the soul - with veils over their heads. They are led, with a knotted cord, by a big swaggering Cupid holding a blazing torch, and another Cupid holds over their heads a basket - it is a winnowing fan - full of pomegranates, a symbol of fertility. At the right another Eros is busy at what has generally been called the marriage bed, but which is in fact simply a stool on which sacred objects, probably a phallus, had been placed and are about to be unveiled. The objects and the basket and the veils belong to an initiation ceremony, not a wedding, so this is an extraordinary ceremony for Cupid and Psyche. The figures are exquisitely carved - they are no more than 3/4 inch high yet the details even of the hair are lovingly portrayed, [below left] as you can see from this view, which also shows the artist's signature, cut into the stone and not in relief as we might have expected. [Below middle] Another oddity is the way the figures are presented as in a frieze, probably copying some monumental original, yet all other cameos of the period showing parts of a frieze enlarge and rearrange the figures to fill the whole stone. There is also the epigraphical oddity, shared with Felix, of making a Greek phi with a hollow centre. The cameo is not from Mantua but had been given to Lord Arundel by the artist Rubens, who was also a busy collector of gems. It can be traced back into the 16th century at least. It had a Renaissance openwork gold mount of a cable and diamonds, and in the 18th century was given an added mount with big flat stones inlaid, which you see in the electrotype [below left].

Finally, what might be regarded as the prize piece - certainly the one most talked about and copied and yet something of a mystery still. It is a cameo now in Boston [right], and the subject is generally called the Marriage of Cupid and Psyche, which, for a start, is almost certainly wrong. I suppose it was made somewhere in the 1st century AD, not too early, although a case could be made that it is in fact a Renaissance work - but I do not want to confuse you. At the centre we see a chubby little Cupid clutching a dove beside an equally diminutive Psyche with butterfly wings - his love and a personification of the soul - with veils over their heads. They are led, with a knotted cord, by a big swaggering Cupid holding a blazing torch, and another Cupid holds over their heads a basket - it is a winnowing fan - full of pomegranates, a symbol of fertility. At the right another Eros is busy at what has generally been called the marriage bed, but which is in fact simply a stool on which sacred objects, probably a phallus, had been placed and are about to be unveiled. The objects and the basket and the veils belong to an initiation ceremony, not a wedding, so this is an extraordinary ceremony for Cupid and Psyche. The figures are exquisitely carved - they are no more than 3/4 inch high yet the details even of the hair are lovingly portrayed, [below left] as you can see from this view, which also shows the artist's signature, cut into the stone and not in relief as we might have expected. [Below middle] Another oddity is the way the figures are presented as in a frieze, probably copying some monumental original, yet all other cameos of the period showing parts of a frieze enlarge and rearrange the figures to fill the whole stone. There is also the epigraphical oddity, shared with Felix, of making a Greek phi with a hollow centre. The cameo is not from Mantua but had been given to Lord Arundel by the artist Rubens, who was also a busy collector of gems. It can be traced back into the 16th century at least. It had a Renaissance openwork gold mount of a cable and diamonds, and in the 18th century was given an added mount with big flat stones inlaid, which you see in the electrotype [below left].

In Boston now it is bare of all these. It was often drawn, and once the piece was in Britain it attracted a great deal of copying. For example, it appears over the fireplace in a room at Blenheim [below left]; on a royal bed at Kingston Lacy. And it was copied by Wedgwood for his famous blue jasper plaques and so appears on innumerable pieces of furniture in Europe, sometimes with a companion subject which Wedgwood devised for it [below middle][below right].

Wedgwood also made an enlarged jumbo version with more detail in the ground line, for decoration of furniture [right], and this was copied also in Germany. Thereafter, through the 19th century, it and groups of figures from it appeared on innumerable cameos and finger rings which you can still find on E-Bay. This is an art whose subject matter has proved a constant inspiration.

Wedgwood also made an enlarged jumbo version with more detail in the ground line, for decoration of furniture [right], and this was copied also in Germany. Thereafter, through the 19th century, it and groups of figures from it appeared on innumerable cameos and finger rings which you can still find on E-Bay. This is an art whose subject matter has proved a constant inspiration.

The real interpretation of the scene is difficult enough, but an 18th-century cleric declared it a sublime expression of married love ... at the left the Cupid's wings are shrivelled up to show that Love can never fly away.

I rather prefer the caricature version of it, still of the 18th century, by the artist Gillray [left]. His fat little Cupid is Lord Derby, who had just married an actress, as our aristocracy was prone to do, and she is shown as the tall figure beside him, replacing Psyche. The Cupid behind her is giving her a ducal coronet, not a basket of pomegranates, and is wearing a red cap and bells, red perhaps because of the known republican sympathies of Lord Derby - this is 1797. The final comment on this strangely unequal partnership is the torch of the Cupid leading the couple - 'when a lovely flame dies, smoke gets in your eyes' as Jerome Kern observed - our Cupid's flame has expired and become no more than a wisp of smoke.

I rather prefer the caricature version of it, still of the 18th century, by the artist Gillray [left]. His fat little Cupid is Lord Derby, who had just married an actress, as our aristocracy was prone to do, and she is shown as the tall figure beside him, replacing Psyche. The Cupid behind her is giving her a ducal coronet, not a basket of pomegranates, and is wearing a red cap and bells, red perhaps because of the known republican sympathies of Lord Derby - this is 1797. The final comment on this strangely unequal partnership is the torch of the Cupid leading the couple - 'when a lovely flame dies, smoke gets in your eyes' as Jerome Kern observed - our Cupid's flame has expired and become no more than a wisp of smoke.

This is a gruelling subject, and out of Oxford we have recruited the help of Diana Scarisbrick in London who had worked on Arundel and is an expert in jewellery, and Erika Zwierlein-Diehl in Bonn, an acknowledged expert in ancient and later gem engraving. It involves a strong memory for hundreds of images, a lot of research in collections, in books and on manuscripts - a novel pursuit for an archaeologist, but it is also a fun subject. I have long indulged it as a relief from Greek vases or the pursuit of Greeks in the east, and I hope I have shown you something of its allure. There is a little display about the Marlborough gems in the Archive Library upstairs, and there should be a book from Oxford University Press within 2 years, if you save your pennies - and you will need plenty.