Hellenistic gems

Introduction

The Hellenistic period (the late fourth to first centuries BC) commences with Alexander the Great and ends at the transition to full Roman control of the Mediterranean world. It saw the rise and fall of powerful Greek empires and the complexity of historical events is mirrored in the diversity of the art produced. The arts of the gem engraver develop from the Classical in several significant ways, all of which also inform the development of the craft in Roman Italy, and there is no abrupt transition to the styles of the Roman period. Internal evidence for dating and classification is scant and changes in style difficult to pinpoint. As a result the distinction between 'Greek' and 'Roman' is often unclear, if not meaningless.

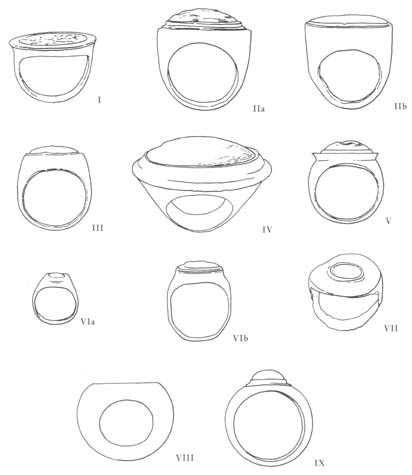

- Hellenistic ring shapes (generally gold). Plantzos Fig. II.

Alexander's conquests opened trade routes from the east, and a greater variety of precious stones, from India and Ceylon, became available for gem engraving. They included the more colourful quartzes (amethyst, sard, onyx, and agate), and the silicates, the garnet group, peridot, and beryl. The chalcedonies common in previous periods remained popular, in particular the bright red cornelians. Another material enjoying a new popularity in this period is glass, often coloured to imitate stones.

Some of the latest classical scaraboids had the intaglio cut on their convex backs. This use of the curved surface, and a preference now for making ringstones rather than larger gems for setting in mounts (and so pierced) typify the Hellenistic. The most distinctive shape is the long oval ringstone, met occasionally in the earlier period but now considerably larger. The shape lends itself to the depiction of slender standing figures. Other shapes are oval or circular, mostly with flat backs, but also with concave or convex. The numerous head and portrait studies seen on the circular gems probably indicate a strong influence from contemporary coinage.

Abbreviations in this section:

AGDS |

Antike Gemmen in deutschen Sammlungen. |

GGFR |

J. Boardman, Greek Gems and Finger Rings: Early Bronze Age to Late Classical (1970). |

Ionides |

J. Boardman, Engraved Gems: the Ionides Collection (1968). |

Oxford |

J. Boardman and M. L. Vollenweider, Catalogue of the Engraved Gems and Finger Rings in the Ashmolean Museum, vol. 1, Greek and Etruscan (1978). |

Plantzos |

D. Plantzos, Hellenistic Engraved Gems (1999). |

Zazoff |

P. Zazoff, Die antiken Gemmen (1983). |

Alexander

Alexander the Great himself selected the artists to create his official portraits, if we are to believe the literary sources. Thus, his court gem-engraver was Pyrgoteles, but it is clear that many others engraved his image, which became even more widely distributed after his death, when it was officially represented on coins for the first time.

Oxford 280 (1892.1499) GGFR, pl. 998; Plantzos 164; Tourmaline (yellow, purple) 24x24mm.

One of the earliest gems with a likeness of Alexander is this stone in Oxford, showing him with the horns of Zeus Ammon, possibly cut shortly after his death in 323 BC. He had visited the sanctuary of Zeus Ammon in 332 BC and the assimilation of the horn attributes had gained political implications. The small inscription below the neck is apparently Indian, either the name of the owner - perhaps a native ruler in a part of India where Alexander was active, or the maker of the gem. The material is rare for gems and of Indian provenance.

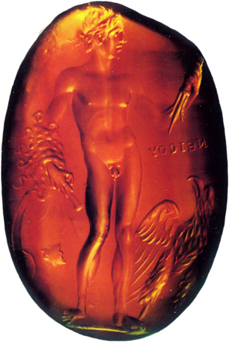

St Petersburg. Plantzos, pl. 29, no. 164. Carnelian. 20mm.

A ruler, probably Alexander, portrayed as Zeus with his eagle, and holding a thunderbolt and aegis. Signed by the artist Neisos, probably still 1st century BC.

Other royal portraits

Real portraiture emerged for the first time in the Hellenistic period, usually of a ruler or his consort. The heads combined realistic features in a somewhat idealised manner, with royal and sometimes divine attributes. The royal portraits on coins ensured their value and authenticity, and the continuation of similar types over generations suggested stability to their subjects. Alexander's portrait served as a prototype, and engravers, for both coins and gems, emphasised family features.

Florence, Museo Archeologico Etrusco (Plantzos 85) Tassie 9757, Amethyst 26x18mm, convex face.

A portrait of Mithridates Eupator Dionysos, who became king of Pontos in 120 BC. It is almost identical to the coin portraits issued in the first half of the first century BC and shows the ruler in the familiar heroic pose, with untamed hair falling down his neck and the royal diadem-bands flying. The attributes borrowed from Alexander's portraits promoted the image of youthful energy and certified his role as a successor.

Among the Hellenistic royal families only the Ptolemies in Egypt depicted a substantial number of their non-ruling queens on coins and gems, sometimes assimilated to a goddess. A general or family Ptolomaic portrait type seems recognizable in the features of many gems.

Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery 42.1339 (Plantzos 30) Garnet, height 20, convex face.

This stone in Baltimore shows a female member of the Ptolemaic family, signed by the artist Nikandros. It shows Berenike II Euergetes wearing a chiton, himation, and a necklace.

Oxford 282 (Fortnum FR. 36) Gold set in iron ring, 25x21mm, flat face

This ring shows another portrait, again probably of a Ptolomaic queen, showing her head in profile. The hair in horizontal plaits (the so-called 'melon-coiffure') is tied at the back in a chignon. The strong features, the striking nose, big eyes and the neck are well known family characteristics known from coins.

Dionysos and his circle

Representations of Dionysos, satyrs and maenads, are particularly popular in all the arts of this period, and some rulers identified themselves with the god. The cult of Dionysos was under royal patronage at many Hellenistic courts and gained particular importance in Egypt when Ptolemy XII pronounced himself the 'New Dionysos'. It is not always clear if a complete identification or merely an association is intended. Ptolemaic kings and queens were recognized as living gods, as were their Pharaonic predecessors, and assimilated to various gods and goddesses during their lifetimes.

Paris, Cabinet des Medailles (Plantzos 26) Onyx 36x28mm, flat face.

The features of the Dionysos on a gem in Paris, seen as bust in profile, wearing a chlamys, with long hair and ivy wreath, resemble a member of the Ptolemaic family.

Oxford 295 (1892.1497) Olivine 18x16x5mm, convex face and back.

The head of the maenad on the gem in Oxford is one of the numerous members of the circle of Dionysos popularly depicted on gems of the whole period. The head is shown in profile, the hair loosely gathered to a small knot low on her neck and held in place by a wreath of ivy and topped by a small bunch of grapes.

Oxford 315 (1892.1562) (Plantzos 603) Rock crystal (15)x15x5.5mm, convex on both sides.

The bust of Silenos in three-quarter view is probably a forerunner of the frontal head of Dionysos, a popular type of the first century BC. He is shown with a wreath of ivy and grapes crowning his bald head and the fillets tying it are visible above each shoulder. A mantle loosely covers his shoulders, leaving his chest bare.

Erotes

In the Hellenistic period Eros is more often represented as a baby, not a youth as before. He forms part of the entourage of Dionysos, as well as attending his mother Aphrodite.

Oxford 354 (1941.623) Clear glass 12x10.5x2mm, flat face, convex back.

Eros and Psyche (with curved wings) are shown running in close embrace in three-quarter view. They are naked apart from a shared mantle draped over their arms. Eros holds a wreath, and beside Psyche is a small altar with flame.

Oxford 357 (1892.1429) Garnet 12.5x8.5x3mm, flat face and back.

Eros riding on a goose, a branch held behind him like a whip.

Various deities

Oxford 351 (1892.1508) Cornelian, 17x15x4mm, slightly convex face and back.

The image of Zeus with ram horns became a popular representation of the god after Alexander the Great was designated the son of Zeus Ammon at the Oasis of Siwa. The head of the god is shown in three-quarter view. This contemplative and passive image of the Zeus is another departure of the Hellenistic period. Earlier representations of the god generally show him active and alert.

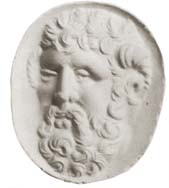

Badisches Landesmuseum, Karlsruhe; Plantzos 384 (Ionides 15; GGFR 997) Amethyst 22.5mm, flat face, convex back.

Not all gods are immediately identifiable. The head of the bearded god wearing a fillet on this gem probably shows the god Poseidon. It is inscribed with the letters P and Y.

Plantzos 510 (Ionides 43) Cornelian 14mm, convex face.

A popular motif of the late Hellenistic period is the bust of a young woman with long wavy hair, her bare shoulders seen from the back, her head shown in profile. The soft folds of the himation framing her shoulder were interpreted by earlier scholars as water and the figure was identified as the personification of the calm see, Galene. The crescent moon added on this gem, however, clearly identifies her as Selene.

New gods

The god Sarapis was an invention of Ptolemaic Egypt. He is popular on Hellenistic gems, often as double-portrait with the Egyptian goddess Isis. Sarapis is often identified with the king, while, from Kleopatra I onwards, the portrait of Isis often appears with royal features. Both deities become endowed with a plethora of new attributes and functions, losing their distinct spheres of action to become more general purveyors of Good Fortune.

Berlin AGDS II 93 pl. 45, 213 (Zazoff 46.8) Cornelian, 218x156x52mm, face and back convex.

The bust of Sarapis in three-quarter view is of the second-century type. He wears full forelocks (anastole) and the defining basket (kalathos) on his head. In later periods the shaggy hair becomes a less common feature. This type clearly derives from sculpture rather than coins or other gems, which usually show the head in profile.

Oxford 290 (1892.1572) (Plantzos 52) Jacinth 13.5x10.5x3mm, flat face and convex back.

A portrait of Kleopatra I, with the horns-and-disc crown of Isis, wearing her hair in Libyan locks, tied with a diadem. This type seems to have been preferred to the traditional Egyptian representation of Isis with the falcon headdress.

Private collection, Garnet 19x15x3mm, flat face, convex back.

Another goddess conceived in the fourth century BC is Tyche, the goddess of Fortune. Her characteristic attributes, such as the cornucopia overflowing with fruit and cakes, show her in her positive image as provider of Good Fortune. It comes as no surprise that she was also worshipped as city protectress, wearing a crown of turrets, as on the head shown in profile on a garnet.

Herakles

Herakles remains the favourite hero of the period, for his moral virtues and his strength in combating monsters and other adversaries. Rulers, from Alexander on, were often assimilated to him. The bearded heads and figures derive mainly from the sculptural type introduced by Lysippus in the fourth century.

Oxford 310 (1892.1335) Garnet (10)x10x2mm, convex face, concave back.

A naked, muscular Herakles with raised club fights the Nemean lion. He is shown bearded and with a laurel wreath on his head.

Oxford 297 (1921.1233) (Plantzos 388) Pale cornelian 19x13x4mm, flat face and back.

This gem shows the head of a young beardless Herakles in profile. The lion-skin is pulled over the back of his head, the front paws knotted under the chin.

Standing figures

The long oval shape for a ringstone was a particular favourite of the Hellenistic period. The most successful way to fill the field was with a standing figure, often leaning on a column or tree-trunk and, through various attributes, characterised as a heroic or divine. Deities are by far the most numerous choice, among them Aphrodite, Athena, Apollo and Dionysos being especially popular.

Oxford 376 (1892.1515) (Plantzos 276) [GGFR 1002] Cornelian 35x22x4mm, convex face, flat back.

A typical example is a woman leaning on a column. Her head is shown in profile, her body in three-quarter view turned the other way, one leg crossing the other. She wears a high-girt sleeveless chiton and she holds her himation, swathed round her legs, away from her body. Her crown (stephane) and the staff with flowing ribbons mark her as a goddess, Aphrodite.

Oxford 336 (Fortnum FR.130) (Plantzos 161) Garnet 17x10.5mm, convex face, set in solid gold ring.

A garnet in Oxford shows Apollo facing to one side with his body in three-quarter view. He holds a kithara in one hand, in the other a plectrum. His dress is the high-girt chiton with long sleeves, with a long cloak draped loosely behind him: the usual dress for a kithara-player. His hair is rolled up and tied at the back. Several variations of the type, Apollo Kitharoidos, are known, and some may well copy sculptural types of the day.

Oxford 303 (1892.1573) (Plantzos 309) Glass (violet) 34x22mm, convex face, set in ring.

Not all versions of the standing figures are executed with the same skill and attention to detail. The goddess in the high-girt peplos depicted on a glass gem roughly follows the rules observed on the stones of better quality, but in a very linear, abstract style. In one hand she holds a phiale, in the other perhaps a torch. The poor quality of the engraving and the use of glass instead of precious stone indicate a piece made for the less wealthy.

Animals

Interest in and close observation of animals and insects were apparent in earlier periods of gem engraving and remain strong inspirations for gem devices. The significance of the images is not always clear.

Oxford 337 (1910.97g) (Plantzos 634) Cornelian 11x8.5x2mm, flat face and back.

The hawk standing in profile on a ground-line on this gem is identified by the Egyptian double crown placed on its head. The image was adopted by the Ptolemies as personal symbol.

Oxford 33910 April, 2012ck.

The significance of an ant shown from above is more difficult to fathom. Many simple devices on small garnets seem primarily chosen for decorative purposes. This does not preclude some personal meaning to the owner, for example a pun, a star sign, or admiration for a virtue represented by the animal, in this case perhaps the industry associated with ants.

Signatures

Several gem-engravers of the Hellenistic period have signed their work. All are of high quality and many, as the Berenike II by Nikandros (see Other Royal Portraits), portray rulers of the Hellenistic courts. Literary sources suggest that some gem engravers profited from royal patronage. The most famous of these, only known to us from literature, was Pyrgoteles, the engraver favoured by Alexander the Great. It seems that the work of selected craftsmen was specially commissioned and valued highly, in particular at the beginning of the Hellenistic period. Signatures become much rarer as the period progresses, probably a symptom of changes in patronage and perhaps even of the social standing of the artist. More signatures appear again at the end of the period when the interest shown by Roman patrons seems to have opened new possibilities for Greek engravers.

Athens, Numismatic Museum (Plantzos 71) (Zazoff 54.2) Cornelian fragment.

The portrait of the Seleucid king Antiochos III on a cornelian ring-stone is one of two known pieces signed by Apollonios.