Corinthian pottery - an introduction

Although never as artistically celebrated as Athens nor as militarily renowned as Sparta, the city-state of Corinth was nevertheless a major player in the renaissance of Greece during the first millennium BC, contributing particularly to the development of visual arts which reached its zenith in the 5th century BC. Her favourable geographical location - situated on the Isthmus between the Peloponnese and Attica, with easy access to the Adriatic in the west and the Aegean in the east - and peculiar ability to prosper supported a checkered history from Neolithic times right through to and beyond the sack of Corinth by the Romans in 146BC.

Pausanias' account of his visit to Corinth in the 2nd century AD records the variety of myths long associated with the area - the Sow of

Krommyon slain by Theseus, the brigand Sinis who tore his victims apart

between two flexed pine trees, the foundation of the Isthmian Games by Sisyphus - as well as the many ancient buildings still standing,

from the archaic Temple of Apollo to the Springs of Peirene, from the rich Agora to the Sanctuary of Aphrodite. Strabo's term for these

relics of the earlier city, 'Necrocorinthia', was used by Humfrey Payne as the title for his important 1933 book on Corinthian pottery.

Pausanias' account of his visit to Corinth in the 2nd century AD records the variety of myths long associated with the area - the Sow of

Krommyon slain by Theseus, the brigand Sinis who tore his victims apart

between two flexed pine trees, the foundation of the Isthmian Games by Sisyphus - as well as the many ancient buildings still standing,

from the archaic Temple of Apollo to the Springs of Peirene, from the rich Agora to the Sanctuary of Aphrodite. Strabo's term for these

relics of the earlier city, 'Necrocorinthia', was used by Humfrey Payne as the title for his important 1933 book on Corinthian pottery.

From the 8th century BC, many other local settlements were attracted by the rich coastal plain, the numerous springs, the ports of Lechaion and Kenchriai, and the steep acropolis of Acrocorinth affording protection, with the result that Corinth was in a position to expand, establishing colonies overseas, most notably on Corfu and Sicily, and to pursue greater foreign trade.

The first modern archaeological excavation was undertaken by the Germans in 1886. From 1896 systematic excavations were continued

by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Some Late Bronze Age Mycenaean and early Iron Age Protogeometric pottery has been

discovered, but it is the later Geometric style that is well represented. Corinthian vases made in the first half of the 8th century BC

have been found at the nearby sanctuary of Perachora and Delphi further along the Corinthian Gulf, at Aetos on Corfu, and throughout Sicily

and South Italy, providing archaeologists with evidence for Corinthian exploration of sea routes and for the dating of sites.

The first modern archaeological excavation was undertaken by the Germans in 1886. From 1896 systematic excavations were continued

by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Some Late Bronze Age Mycenaean and early Iron Age Protogeometric pottery has been

discovered, but it is the later Geometric style that is well represented. Corinthian vases made in the first half of the 8th century BC

have been found at the nearby sanctuary of Perachora and Delphi further along the Corinthian Gulf, at Aetos on Corfu, and throughout Sicily

and South Italy, providing archaeologists with evidence for Corinthian exploration of sea routes and for the dating of sites.

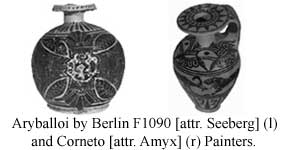

In the late 8th century, when the Geometric style was coming to an end, Corinthian contact with the Near East was a stimulus for the Orientalizing style of Greek pottery. Evidence from excavation of the 'potters' quarter', one mile west of Corinth, would seem to support this resurgent interest in painted wares. The traditionally angular geometric patterns were being replaced with the curvaceous flora and fauna that typify the Protocorinthian style. For much of the 7th and 6th centuries Corinth led the Greek world in producing and exporting pottery.

When Attic wares superceded Corinthian in the mid-6th century, Corinth had left a significant legacy of artistic developments, not only in pottery, but also in architecture, which had thrived under the powerful, aristocratic, Bacchiad family, as Herodotus describes. A monarchy was established by Kypselos in 657, whose successor, Periander, may have been responsible for constructing the stone track (diolkos) by which ships were dragged across the Isthmus. Many wars throughout the ensuing centuries eroded Corinth's resources, and the city fell to Philip of Macedon in 338. Her participation with the Achaean Confederacy in the Second Macedonian War eventually led to her sack in 146, but Corinth was refounded as a Roman colony. By the time Paul had established an early Christian church there in the late 1st century AD, Corinth was once again a splendid city.