Introduction

(adapted from a lecture given by Dr. D.C.Kurtz in the Louvre on 15 November 2000 for a day of lectures on Les collections de moulages: un musee ideal? in association with the exhibition d'Apres l'Antique)

The antique

Taste and the Antique, was written by Francis Haskell with Nicholas Penny almost twenty years ago - in Oxford, when Francis was the University's Professor of the History of Art and Nicholas was Keeper of Western Art in the Ashmolean Museum. In the year of publication, 1981, they held a special exhibition, The Most Beautiful Statues. The centre-piece was the plaster cast of the Borghese Gladiator from the museum's Cast Gallery.

- [View larger image]

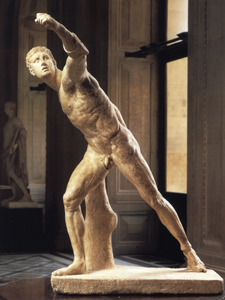

Marble statue of the Borghese Gladiator in Paris

- Cast of the Borghese Gladiator in Oxford

The marble statue of a muscular young man had been known since 1610. One of the reasons the statue became so famous is that it was greatly admired by artists and often used by them as an anatomical model or écorché. Recently restored the statue is a centre-piece of After the Antique - shown above left. To art historians it is the Borghese Gladiator - one of the most influential pieces of antique sculpture. To a classical archaeologist it is a 1st century BC copy in marble of a late 4th century BC statue, made in the tradition of the sculptor Lysippos, and once in the collection of the Borghese.

- Commodus as Hercules

- Artemis of Versailles

- Antinous of the Belvedere

- 'Gladiator'

The sculptures illustrated above, once at St. James's Palace, are now in Windsor Great Park.

Charles I of England was especially pleased to have the 'Gladiator' cast in bronze by his court sculptor Hubert Le Sueur in 1633 because it was the only antique sculpture he could display at St James's Palace which François Ier had not had Primaticcio copy for Fontainebleau almost a century earlier.

From the 15th century through the 19th artists, connoisseurs and students of art knew a relatively small number of statues which had great influence over western Europe and over those parts of the world visited and ruled by western Europeans. Unlike Etruscomania and Egyptomania the passion for the classical antique was much deeper, more widely spread, and much longer lived, because it was an expression of a common European cultural heritage.

In English the etymology of the word antique is uncertain. The Oxford English Dictionary says it could be from the Latin antiquus or, more likely, the French antique, as used from the 16th century. It has come to be used in the singular for Greek and Roman civilisation, and in art to be equated with Greek and Roman sculpture. Art historians tend to group the Greek and Roman together and not to concern themselves with whether an object is a Greek original, a Roman copy of a Greek original, or an original Roman. In contrast classical archaeologists do not use the term and they distinguish Greek from Roman, original from copy.