The origin of the Buddha image remains a topic of much interest, but where does the casket fit within this story? Where and when was it made? Not only are such questions difficult to answer, but the practice of relic cult is in itself a complicated matter. Coins and other objects inside reliquaries can be used for dating, yet these objects were not always buried inside the stupa at the same time as each other. In the event of a re-consecration of relics, a new object could have been added to the original assemblage, and it is not impossible this could have been the case for the Bimaran casket. Needless to say, it is almost impossible to know whether the coins and the objects found in the same assemblage were produced at the same time.

If it is so hard, then, to say when the Bimaran casket was made on the basis of its contents, would it help if we knew who might have made it and where? Does examination of the iconography with its focus on the Buddha suggest that this casket was made in India, the motherland of Buddhism, and imported to Afghanistan? Or was it made somewhere closer to Afghanistan where Buddha imagery was also familiar, at least by the Kushan period? Could it have been made in an urban area where high-level of craftsmanship might be expected? What about the city of Sirkap (Taxila), for example? In short, could the artistic tradition and production techniques employed on this casket tell us something about its maker and place of origin?

Fig. 1 Bimaran casket (BM1900.209). © the Trustees of the British Museum.

Fig. 2 Underside of base of the Bimaran casket (BM1900.209). © Wannaporn Rienjang. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

To begin with, the use of gold as a medium for a relic casket during the first and second century AD is rare in India, but rather common to 'Greater Gandhara' (an area that includes Taxila to the east and eastern Afghanistan to the west). What is not so common amongst the gold relic caskets in Greater Gandhara are the size and decoration of this Bimaran casket. While the height and diameter for the gold (or precious metal) relic caskets in Greater Gandhara commonly measure between 2.0 x 2.0 cm. and 3.0 x 3.5 cm., the Bimaran casket measures 6.5 cm in height and 6 cm in diameter. Gandharan gold relic caskets were generally made of plain hammered sheets of gold. The Bimaran casket was also made of hammered gold sheet but its distinctive characteristic is its rich, figural decoration that includes the Buddha, Brahma, Indra, and another unidentified figure, executed using repoussé and chasing techniques on the body (Fig. 1). Its base was also decorated with eight lotus petals (Fig. 2). The casket was also adorned with with garnet and turquoise inlays. No other relic casket in early India or in Greater Gandhara comes close to the level of this intricate craftsmanship.

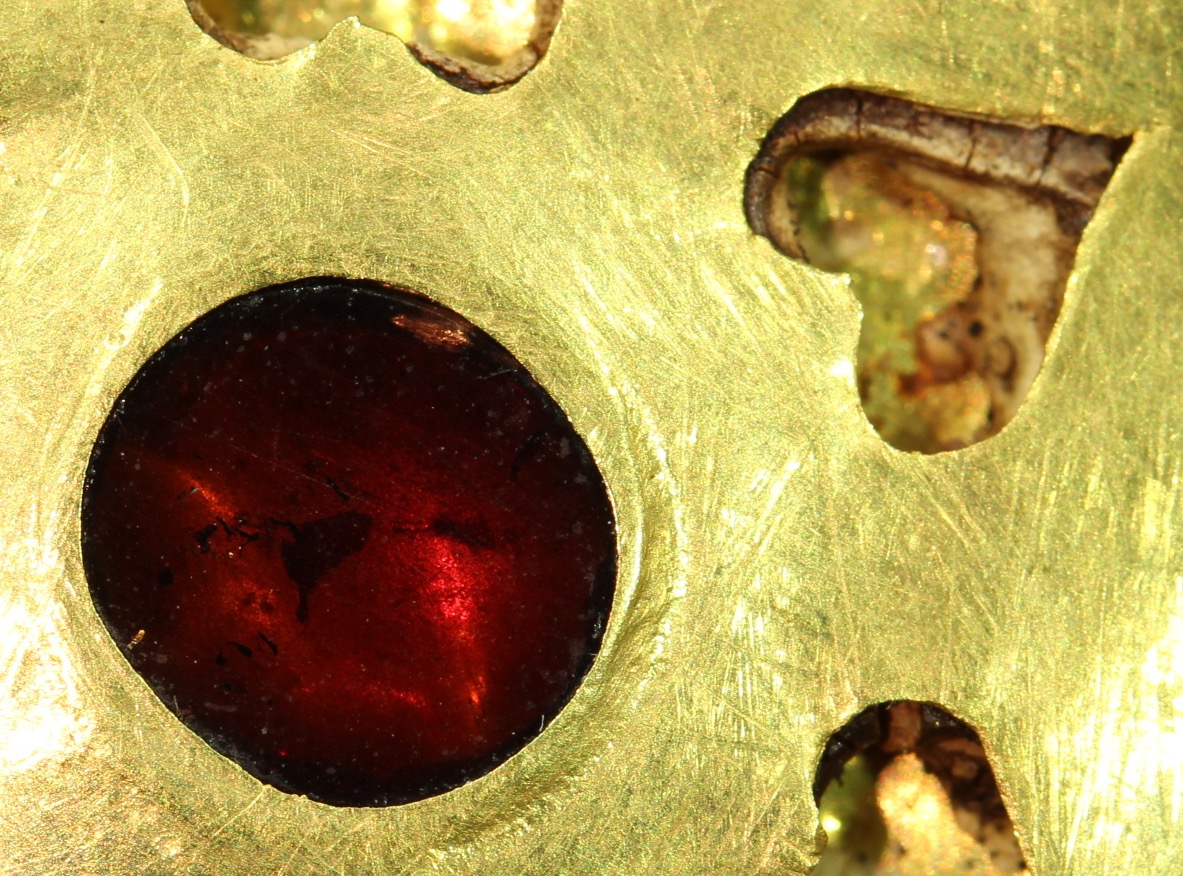

This Lack of parallel objects in India and Greater Gandhara may prompt some of us to link the production of this casket with the Central Asian nomads, whose love of gold and high level of skills in metal-working are well known. A number of gold and silver vessels of high quality craftsmanship were found in the first century AD Royal necropolis in Tillya Tepe, northern Afghanistan (Sarianidi 1985; 2011). There are also parallel objects from this necropolis such as sewn-on items made of gold in similar in fashion to those found in the Bimaran relic deposit (Errington, forthcoming). One feature of the manufacture that links the Bimaran casket with traditions beyond India is perhaps the inlay of semi-precious stones inside sockets that were formed by separate sheets of gold joined to the body by soldering (Fig. 3). This technique occurs on objects associated with Central Asian nomads or people from eastern Iran. Some examples are the gold and silver vessels in the al-Sabah Collection with rows of garnet inlays on the neck (Figs. 4 & 5). The sockets for the inlays on these two vessels were made in the same manner as those on the Bimaran casket. The provenance of the al-Sabah vessels is not known, but the form and craftsmanship of the gold vessel has been associated with eastern Iran or Bactria during the first half of the first millennium AD (Carter 2015: 348-9), while the form and decoration of the silver vessel has been linked to the Seleucid Empire or Parthian Western Asia during late second to first century BC (Carter 2015: 72).

Fig. 3 Socket for the garnet inlay of the Bimaran casket (BM1900.209). Photo © Wannaporn Rienjang. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Fig. 4 Gold vessel in the al-Sabah Collection (LNS 3141 I). Photo courtesy of Martha Carter (2015: 349, cat. 96)

It is not impossible that setting an inlay in this manner was a norm in Central Asia and adjoining areas. Interestingly, a different technique of setting an inlay was employed on a gold relic casket from a stupa in Afghanistan, not very far from where the Bimaran casket was found. This is the gold relic casket from the Ahinposh stupa east of Jalalabad. Unlike those on the Bimaran casket and the above two vessels in the al-Sabah Collection, the garnet inlays on this casket were set on an organic layer between two sheets of gold (Fig. 6). The coins found with this casket date perhaps about a century later, i.e. second/late second century AD (Errington & Fabrègues 1992).

Fig. 5 Silver vessel in the al-Sabah Collection (LNS 1520 M). Photo courtesy of Martha Carter (2015: 72, cat. 7)

Fig. 6 Gold relic casket from Ahinposh stupa (BM1880.29). Photo © Wannaporn Rienjang. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Was the Bimaran casket a product of a Central Asian workshop? Was it made somewhere further away from Gandhara? Or was this technique also common in eastern Afghanistan where the casket was found? These questions remain to be answered and more evidence with provenance is needed. At least what we know is that the iconography of the Buddha and Indian deities are not local to Central and Western Asia during the first century AD. The contrast between production technique and iconography on this Bimaran casket perhaps also positions it as a good example of the variable transmission of techniques and iconography across regions and over time.

[Wannaporn Rienjang, 26/11//2017]

References

Carter, M. 2015. Arts of the Hellenized east: precious metalwork and gems of the pre-Islamic era. London.

Errington, E. Forthcoming. The Buddhist remains of Passani and Bimaran and related relic deposits from south-eastern Afghanistan from the Masson Collection. In: J. Stargardt (ed.) Relics and relic worship in the early Buddhism of South Asia and Burma.

Errington, E. and Fabrègues, C. 1992. Stupa deposit from Ahinposh, Jalalabad district, Afghanistan. In : E. Errington & J. Cribb. The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol. Cambridge, 176-77.

Sarianidi, V. 1985. Bactrian gold: from the excavation of Tillya-Tepe necropolis in northern Afghanistan. Leningrad.

Sarianidi, V. 2011. Ancient Bactria’s golden hoard. In: F. Hiebert & P. Cambon (eds.) Afghanistan: crossroad of the ancient world. London, 211-293